Cementing Motherhood, Embracing Change in the Nicaraguan Revolution

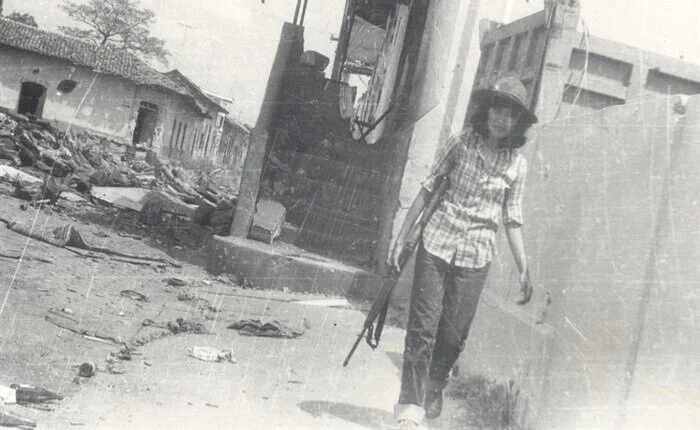

On March 8, 1978, General Reynaldo Pérez Vega walked into Nora Astorga’s apartment expecting a romantic evening. Unbeknownst to him, however, a different plan was set. Vega, a strong supporter of the autocratic regime in Nicaragua, was to be kidnapped and held for ransom by the Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional, known by the more popular name Sandinistas, who opposed the decades-long dictatorship of the Somoza family. When Vega resisted, the Sandinista operatives instead killed him, and the operation vaulted Astorga to a position of prominence within the Sandinista ranks.

The Nicaraguan Revolution, which toppled the Somoza dictatorship in 1979, succeeded because women like Astorga risked everything for the cause. As the Sandinistas moved to take power of a country ravaged by corruption, they encouraged women to become political actors, but they also cultivated a new conception of gender based on motherhood. To reinforce gender norms that favored the revolution, the Sandinistas promoted motherhood as a central role of the revolutionary woman. But women, who had stood alongside men in the fight against Somoza and who now held positions of authority at national and local levels, saw another way. By harnessing participation in healthcare, women continued to seek a revolution that favored gender equity and pursued a truly feminist revolution even as their efforts were met with national and local disapproval.

The new, revolutionary Nicaraguan woman struggled to separate herself from the expectations of motherhood. When Astorga lured Vega to her home, she was a 28-year-old mother of two. If the operation was successful, Astorga knew her role in the revolution would make it difficult, if not impossible, to go back to her children. “It was a difficult decision,” Astorga said of her role in the Vega assassination. “I knew that after that I wouldn’t be able to return to my life, that I wouldn’t be able to return to my daughters—one was six years old, the other two—and that cost me most dearly.”

“To reinforce gender norms that favored the revolution, the Sandinistas promoted motherhood as a central role of the revolutionary woman.”

Like Astorga, many Nicaraguan women experienced the Revolution differently than their male counterparts—faced with a choice between family and activism. Julia García “nearly abandoned” her children as she struggled to be both a revolutionary and a poor mother of five. For García, liberating her country would mean liberating her children, but she struggled to balance the demands of political activism with the demands of motherhood.

The Sandinistas depicted motherhood as a centrally patriotic and democratic activity for Nicaraguan women. The issue of “olive green maternity dresses,” worn by women working both for the army and other branches of the Sandinista government, only further cemented the amalgamation of the two.They also encouraged the idea of revolutionary motherhood through propaganda. The Asociación de Niños Sandinistas (Association of Sandinista Children) created the poster entitled “Felicidades Mama: Gracias Madre por Defender Nuestra Alegría” (Congratulations Mother: Thank you for protecting our happiness). In the cartoon, two young children stand next to their mother who is carrying a baby. A gun adorns the woman’s shoulder and a puppy trails behind the cheerful family. Another famous photo, taken in 1982 and known as “madre armada y niño” (armed mother with child), similarly depicted an armed Sandinista woman nursing her child. These images illustrated what the new Nicaraguan woman should look like. She should be political, a Sandinista, and willing to take up arms on behalf of her country. At the same time, she should be mothering the next generation and shouldering the burden of teaching Nicaraguan youth to be Sandinistas.

While the revolution continued to enforce strict links between motherhood and revolutionary womanhood, Nicaraguan women now knew they had a powerful voice and a capacity for change. Of women’s new understanding of their political and social roles, Astorga stated, “Women won’t be apathetic again.” Throughout the decade of Sandinista rule, women eschewed apathy by pursuing new opportunities for leadership and community development. Because of how significantly the new health system impacted women, it became a significant site through which they developed feminist revolutionary ideals. The health system was integral to women’s revolutionary agenda in part because of the many new positions, at both national and local level, available under the Sandinista’s popular health system.

Felicidades Mamá offset print, late 1970s], [Folder 8], [Jane Norling and Lenora (Nori) Davis Collection], Special Collections and Center for Southwest Research, University of New Mexico Libraries.

Between 1980 and 1990, the two leaders of the Sandinista Ministry of Health (MINSA) were women. Lea Guido (1980-1985) and Dora María Téllez (1985-1990) shaped the state of Nicaraguan health in significant ways that often opened avenues for women’s advancement in health care. Guido focused on creating Popular Health Commissions that expanded the role of brigadistas de salud (community health volunteers), a majority of whom were women. Known as ‘Comandante dos,’ or Commander Two, Téllez served as a leader of the revolution in addition to her later role as Minister of Health. A significant figure within the Sandinista ranks, Téllez noted that “the [Sandinista government] was a structure that also was under an important machismo influence.” But Téllez supported women in the health system in ways that broke with this machismo.

As patients, women benefited from Téllez’s 1986 reform that allowed women to undergo a sterilization procedure without a husband’s consent. This was, according to historian Kristin Cheasty Anderson, “the first time in the nation’s history” in which women were granted “physical autonomy.” Téllez also championed greater opportunities for women in healthcare through programs like midwife training, which aimed to both improve maternity care and to train more women for healthcare work.

On a local level, women embraced the budding popular health system. As men continued to be siphoned away from communities to fight against the U.S.-backed Contras, women stepped up to take on the many new healthcare roles instituted during the Guido and Téllez ministries. Aynn Setright, a U.S. solidarity activist who worked alongside many Nicaraguan women, noted that “women’s reproductive health was a big thing for them, they always came back to that.” Women’s cooperatives, which were democratically run groups of women united around social, economic, and cultural issues, worked to improve local health systems and create programs that remained important for decades—focusing largely on maternal and child health. In the community of Mulukukú, the Maria Luisa Ortiz Women’s Cooperative started a health clinic that focused on disease prevention and promoting women’s and children’s health. But women’s cooperatives, while politically encouraged to focus on these issues of motherhood, often stepped outside of those bounds as well. Cooperatives also focused on combating domestic violence, promoting access to abortions, and expanding sexual equality under a regime that saw these goals as antithesis to the revolution.

“Because of the deep tie between women and motherhood, the new popular health system became an important site in which women defined their own ideas about the revolution and embraced their capacity for leadership.”

The health brigadista, often a young woman without formal education, was an “emblematic representative of the Nicaraguan model of participation” in popular health. In volunteering to serve communities throughout Nicaragua, health brigadistas received medical training from popular organizations with materials provided by the Ministry of Health. Under Guido, the Ministry of Health trained 30,000 brigadistas in 1980 alone. The brigadista program not only extended the reach of the new popular health system into rural communities but also gave young women an opportunity to become leaders, community builders, and health workers.

Under both Téllez and Guido’s leadership, midwives, who in 1981 assisted in over half of all rural deliveries, gained greater recognition and training. These women, who already held important roles in their communities, now had an authority backed by the national health system. The Ministry of Health offered training for midwives in “how to care for pre- and post-natal mother; how to detect high risk pregnancies and refer them to the health center; how to deliver low risk pregnancies using aseptic techniques.”

The Nicaraguan Revolution brought incredible liberation to a country long ravaged by dictatorship. New conceptions of womanhood came into play that broke with traditional gender norms, though not completely. The Sandinistas encouraged women to be political actors, but they also wanted women to embrace motherhood in ways that benefited revolution. The health system was a means to circumvent the disconnect between those in power pushing for revolutionary motherhood and the women involved in the movement—an avenue to gain greater influence over the revolution, political activism, and expectations of motherhood. Because of the deep tie between women and motherhood, the new popular health system became an important site in which women defined their own ideas about the revolution and embraced their capacity for leadership.

Further Reading

Global Feminisms Project. “Nicaragua.” University of Michigan (2011).

-Dora María Téllez. Interview by Shelly Grabe.

-Mónica Baltodano. Interview by Shelly Grabe.

-Bertha Inés Cabrales. Interview by Shelly Grabe.

Randall, Margaret. Sandino’s Daughters Revisited: Feminism in Nicaragua. (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1994).

Image credit: Photo taken during the Insurrección de León 1979 (Wikimedia Commons | Public Domain)

![Felicidades Mamá offset print, late 1970s], [Folder 8], [Jane Norling and Lenora (Nori) Davis Collection], Special Collections and Center for Southwest Research, University of New Mexico Libraries.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5674a2570ab377c9815a1bf3/1610560712782-JYR5WDGRFLIE356ZTHHI/Felicidades+Mama+poster+featuring+a+woman+in+military+garb+surrounded+by+children+and+holding+a+baby.jpg)