Colonial Panic Over Syphilis in Uganda

“Owing to the presence of syphilis, the entire population [of Uganda] stands a good chance of being exterminated in a very few years, or left a degenerate race fit for nothing,” wrote Royal Army Medical Corps Colonel F.J. Lambkin in 1908.

When the British government took formal control over Uganda in 1894, they decided that the colony needed to become financially self-sufficient. The government created a system where laborers grew and sold cash crops such as cotton, coffee, and tobacco to pay the taxes needed to sustain the administration. For this system to succeed and benefit the administration, a healthy and growing population was critical. However, at the turn of the 20th century, the population appeared neither healthy nor growing. The administration was extremely concerned by sluggish population growth, stalling birth rates and high rates of infant mortality. They believed sexually transmitted diseases (STDs)—particularly syphilis—were the main causes.

Fearful of declining birth rates, the British Colonial Governor for Uganda had directed Colonel Lambkin to conduct a survey into syphilis in the colony. The result was “An Outbreak of Syphilis In a Virgin Soil,” a survey detailing the perceived threat of syphilis, which he peppered with moralizing and racist language. The survey focused on the region of Buganda, the economic center of the colony and where most early anti-syphilis interventions would be implemented. It outlined an apparently dire situation, stating that syphilis was the chief cause of infant mortality and that as many as 90 percent of the population were infected in certain districts.

Lambkin’s claims were incorrect and based more on racialized assumptions than concrete data. Following its imperialist attitudes towards race, health, and motherhood, the government implemented a coercive campaign focused on identifying and treating syphilis.

“Syphilis was now not only viewed as a health problem but as a moral problem, and they began a propaganda campaign against presumed “immorality.”

In the U.K, the public was also putting pressure on the government to eradicate syphilis in Uganda for humanitarian reasons. The administration decided it had to act. Following Lambkin’s survey, the government introduced the 1909 Dangerous Diseases Ordinance, followed by the Venereal Diseases Rules in 1913, making it a legal requirement for individuals with a venereal disease to undergo treatment. For syphilis, the main treatment was an extremely painful intramuscular injection of mercury with potentially dangerous side effects.

Cases of syphilis were identified through a range of methods, including humiliating public inspections and paying tribal chiefs to report cases of syphilis. Various groups— such as missionaries and local chiefs—used the campaign against syphilis to try and improve their own position within the colony and increase their power. By the late 1910s, there was greater enforcement regarding STD examination and treatment in Uganda than anywhere else in the world. As well as being forced to receive a full course of treatment, the infected were banned from marrying, having sex, or trading goods during their treatment. Failure to meet these conditions or complete treatment could lead to imprisonment or fines, and patients could be forced to finish their courses of treatment by police.

After the end of the First World War, the colonial administration began a stronger approach and incorporated new tactics into their anti-syphilis campaigns. Syphilis was now not only viewed as a health problem but as a moral problem, and they began a propaganda campaign against presumed “immorality.”

While the colonial administration funded these campaigns, termed “social purity campaigns”, the implementation was led by religious missionaries. The campaigns aimed to create feelings of guilt amongst those believed to be suffering with STDs, particularly syphilis. The government paid medical missionary Albert Cook to tour Uganda to give lectures and create materials in local languages on the dangers of venereal diseases, focusing on sterility, abortion, infant mortality, and the ‘extinction’ of the ‘nation.’ These lectures connected imperial attitudes towards health with ideas of motherhood and fears about demographics and the future of the nation. Propaganda campaigns also often focused on the actions of sexually active individuals, aiming to make them healthier and more fertile.

Alongside the anti-syphilis interventions and propaganda campaigns, the colonial government increasingly intervened in the lives of women and families. In 1918, the British government launched a Maternal Training School in collaboration with missionary groups. The school was run by the Church Missionary Society (CMS), which represented various British evangelical denominations, with the board of governors initially including representatives from the CMS, Catholics, and the colonial administration. While general early colonial policy had focused on areas such as war, exploration, and economic production—areas traditionally seen as male domains—the panic over birth rates and the size of the labor force had caused a shift in policy to focus on population growth and the lives of women and young girls.

The Maternity Training School trained teenage girls as midwives who would be sent to maternity centers across the country and could help women through childbirth and teach new mothers how to care for their children. The aim of the school was not just to improve health but to transform Ugandan society. By 1926, there had been a rapid increase in midwife training, though only around 2,000 of 16,000 live births in Buganda were attended by certified midwives. Outside of Buganda, MTS-trained midwives were even more scarce. The midwives were often isolated in communities due to their new education and were deliberately avoided by expectant mothers.

The Maternity School was a means for the colonial government to impose its ideas on how to improve maternal health and to increase birth rates. The school also gave religious missionaries power to push their assumptions about health and morality. As well as creating a channel to receive official funding and to alleviate suffering, missionaries used the schools to emphasize Christian education and teach students to be “morally pure.” The schools had a complex relationship with the trainee midwives. While midwives were lauded as “saviors,” the centers also treated midwives as minors, even after graduation and did not approve of midwives trying to establish equality with European missionaries. Pupils were also treated strictly and could be expelled for perceived “immorality,” such as sexual activity or becoming pregnant.

Simultaneously, many colonial administrators and missionaries viewed African mothers as incompetent, stating that they behaved as though they were less than fully human. These racist beliefs were used to justify the forced gynecological examinations of Ugandan women; a similar Contagious Diseases Act had recently been repealed in the U.K. on the grounds that it was dehumanizing to women. These same standards were not applied in Uganda.

“The association between syphilis and shame deterred sufferers from seeking treatment and the anti-syphilis programs were also run by male doctors, which further increased suspicion amongst women.”

However, the British government in Uganda found it difficult contact women to conduct forced examinations and to treat them. Not surprisingly, women viewed the dehumanizing examinations and coercive treatment with suspicion. The association between syphilis and shame deterred sufferers from seeking treatment and the anti-syphilis programs were also run by male doctors, which further increased suspicion amongst women. Women were also often shielded by their relatives from examination and treatment; women performed the bulk of domestic work and repeated appointments could cause serious disruptions to the running of households.

Margaret Lamont, the only female doctor in the British administration in Uganda, was dismissed in 1922 after she criticized the treatment of Ugandan women. This sparked protests in the U.K. as well as criticism from the British press. The growing scandal led to an inquiry where medical groups strongly criticized the figures cited in Lambkin’s report. The idea of 90 percent prevalence of syphilis was dismissed as ridiculous, as it was based on the examination of individuals already believed to be suffering from STDs. Instead, the Association for Moral and Social Hygiene estimated its incidence was between 10 to 20 percent, the same rate as in the U.K.

The Colonial Office ordered the compulsive measures to end, and the anti-STD campaign was increasingly merged in the general work of the medical department in Uganda from 1923. The focus of anti-syphilis measures moved away from propaganda campaigns and towards medical procedures. New medical officers adopted a more practical approach to STDs, which they viewed as one of a range of preventable diseases, and at Uganda’s flagship hospital, medical testing for syphilis became more common. However, the belief that syphilis was widespread and associated with “immoral” behavior would take a long time to unlearn.

Further research has since shown that misdiagnosis was rife and syphilis was often confused with other conditions, such as endemic yaws (a bacterial, childhood infectious disease), gonorrhea, or even non-sexually transmitted forms of syphilis. By the 1930s, the medical establishment no longer perceived syphilis as the primary cause of infertility. There was greater diagnostic and scientific knowledge, mass treatment of syphilis at ante-natal clinics and a general improvement of the population’s health.

However, the colonial government was still concerned by infertility and maternal health in the late colonial period (1930s-1950s). Rather than shaming “immoral” mothers, health campaigns instead focused on “ignorant” mothers, perceived to be reliant on supposedly unsafe local customs. Colonial healthcare was entering a new phase, though many underlying assumptions about race, motherhood, and health remained.

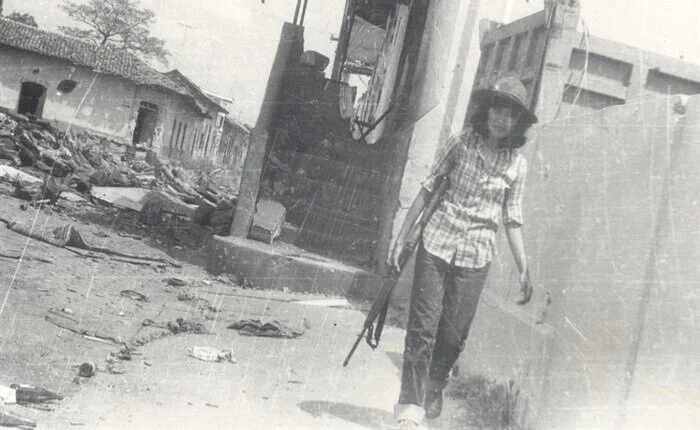

Image credit: Medical missionary and patient at the Church Missionary Society Hospital at Mengo, Uganda (Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images | CC BY 4.0)