Episode 4: Technology and Women's Labor

1:26:49

Hosts: Anna Reser, Leila McNeill, and Rebecca Ortenberg

Guest: Marie Hicks

Producer: Leila McNeill

Music: nononoNO

In this episode, Anna and Rebecca challenge us to expand our definition of technology to include women's work with technological foods and sewing. Leila breaks down the class and labor implications of a net neutrality rollback and urges feminists to include net neutrality in their activism. And finally, guest Dr. Marie Hicks joins us to talk about their book Programmed Inequality: How Britain Discarded Women Technologists and Lost Its Edge in Computing.

Show Notes

Technological Food and Women's Labor by Anna Reser

Nicholas de Monchaux, Spacesuit: Fashioning Apollo (MIT Press, 2011).

New Poll: Americans Overwhelmingly Support Existing Net Neutrality Rules, Affordable Access, and Competition Among ISPs

More than 60 million urban American's don't have access to or can't afford broadband internet by Rani Molla

Internet/Broadband Fact Sheet by Pew Research Center

13% of Americans don't use the internet. Who are they? by Pew Research Center

Net Neutrality is a Feminist Issue. Here's Why. by Sarah Mirk

Man Develops App to Reveal What Women Look Like Without Makeup by Madison Malone Kircher

Sewing Science, Sewing History by Rebecca Ortenberg

Dr. Marie Hicks website

Marie Hicks, Programmed Inequality (MIT Press, 2017).

Further Reading

Gutting net neutrality is a death knell for the resistance by Sarah Kendzior

Ruth Oldenziel and Karin Zachmann, Cold War Kitchen: Amercanization, Technology, and European Users (MIT Press, 2011).

Jessamyn Neuhaus, “The Way to a Man’s Heart: Gender Roles, Domestic Ideology, and Cookbooks in the 1950s,” Journal of Social History, vol. 32, no. 3 (1999): 529-555.

Glenn Sheldon, “Crimes and Punishments: Class and Connotations of Kitschy American Food and Drink,” Studies in Popular Culture, vol. 27, no. 1 (2004): 61-72.

Margot Lee Shetterly, Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space Race (Harper Collins, 2016).

Transcript

Transcription by Rev.com

Rebecca: Welcome back to the Lady Science Podcast. A monthly deep dive on topics centered on women and gender in the history and popular culture of science. With you every month are the editors of Lady Science Magazine.

Anna: I'm Anna Reser, co-founder and co-editor in chief of Lady Science. I'm a writer, editor and PhD student studying 20th century American culture and the history of the American Space Program in the 1960s.

Leila: I'm Leila McNeill, the other founder and editor in chief of Lady Science. I'm a historian of science and freelance writer with words in various places on the Internet. I'm currently a regular writer on women and the history of science at smithsonian.com.

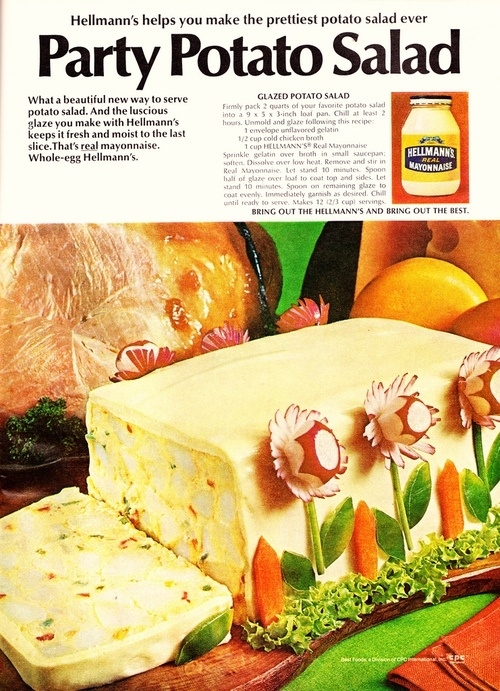

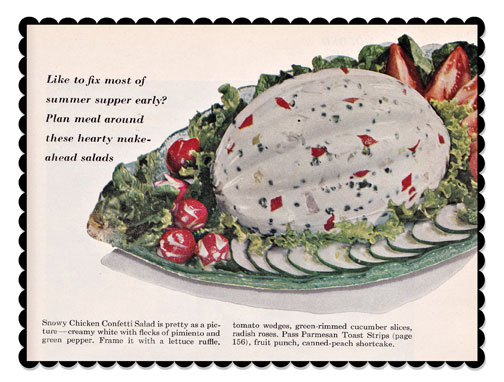

Rebecca: And I'm Rebecca Ortenberg, Lady Science's managing editor. When I'm not working with the Lady Science team, I can be found writing about museums and public history around the Internet, and managing research projects at the Chemical Heritage Foundation in Philadelphia. For this episode, we are focusing on technology. So you know all of those awful mid-century molded jello salad things? Or those mayonnaise-frosted sandwich loafs? Or the thick casserole sopping with condensed can soup? Anna is going to share what those foods tell us about patriotism, modernity and of course technology. Leila will talk about how net neutrality intersects with class and labor and explain why a neutral and equal Internet is essential to the feminist movement. And I'll be sharing a family story about fashion, engineering and feminist history in post-World War II California.

Rebecca: To wrap up the show, historian of technology and writer Dr. Marie Hicks will be joining us to talk about gender and sexuality in the history of computing.

Anna: Okay so I want to talk about horrible mid-century food, which is a fairly well known obsession of mine. It's all Kim Stanley Robinson and jello salads over here. That's all I spend my time thinking about. But I wrote a piece, sometime in the past I wrote a piece for Lady Science about these kinds of foods and how we can think of them as technology and by doing so, we can sort of reframe the history of the housewife and the role of women in kind of shepherding modernity into the home and ensuring that it's a ... being enacted at home as well as in the wider business or political structure. So it's a story mostly about the United States because that's what I study. So first I just want to talk about what these foods are. I think maybe people in the US who grew up like in the Midwest or in the South are familiar with these kinds of foods. They're made from manufactured foods which are relatively new in the post-war period.

Anna: There are important changes in the way that food is manufactured and packaged in the post-war period that allow you to have so called convenience foods. So, instead of buying fresh produce you could buy frozen produce. You can obviously buy canned produce for much of the 20th century. But like frozen produce becomes much more readily available and other kinds of foods that are prepared in ways that wouldn't be possible earlier. Certain kinds of like freeze drying. I'm thinking of like the crispy fried onions you put on a green bean casserole. Things like that, that can be produced on a massive scale. Packaged. Put into grocery stores. And so along with all of these prepackaged and manufactured foods, you get extensive libraries of cookbooks and recipes for how to work with these foods. And the cookbooks are pretty prescriptive about not only how you can physically work with these foods, but how you can incorporate them into the expectations that your family would have about what constitutes like a proper meal.

Anna: And that you should use these new foods but you should try to disguise them as much as possible, as fresh foods, or that kind of gets filtered in this weird way as you move into the 50s and 60s that you're not actually disguising them as quote on quote, "real food" but you're like making them in the shape of real food in this very strange way. So like I've seen a recipe for like a hot dog crown roast. But a lot of technological foods while they're marketed to women this period as being convenient, the work that you have to do to make them acceptable to what your family supposedly expects of you, and by family, you mean like your husband, expects you to prepare a meal in a certain way. There's all kinds of interesting work that's been done about gender roles and food and like performing various ideas of plenty and sort of American idealization of agriculture.

Anna: But that gets kind of weirdly distorted in the post-war period with the introduction of these kinds of food. So the reason that I cast these kinds of foods as technological is one, because of the way they are made and the changes in manufacturing that allow for mass production of things like mayonnaise, which you can make at home fairly easily. Even more easily if you have certain kinds of appliances. But once it becomes available and shelf-stable, there's no reason to stand over a bowl with a whisk. So these foods are technological in that they are made by new manufacturing technologies. But I think that where things get really interesting and where you can use these kinds of foods as a way into talking about housewives and these ideas of modernity and performing this kind of American interest or faith in technology is talking about the foods themselves as technologies and the women who use them and who experiment with them and transform them into these elaborate sculptural structural marvels of gelatin and other things, is by talking about them specifically as technologies and the women using them as embracing a kind of technological modernism.

Anna: So, mayonnaise is a good example because in a lot of the recipes that I looked at, mayonnaise is specifically used as a way to decorate the foods but also to keep them fresh. So, you would frost the sandwich loaf with mayonnaise because mayonnaise goes on a sandwich.

Leila: I'm sorry. Saying mayonnaise and frost in the same sentence is just ...

Anna: Slathered on there. But it's meant to keep the sandwich loaf fresh so that you can make it ahead of time. So it's a technology in the form of food that you can buy conveniently to augment your labor in the kitchen, so that you can make things ahead of time so you have your garden party the next day. Make your sandwich loaf the night before. It doesn't get dried out. I also saw mayonnaise used that way to like, for a guacamole recipe that was in the Better Homes and Gardens cookbook that I guarantee you no person who was not white has ever even seen that cookbook before it went to print. So you mix all of the stuff and then you put a layer of mayonnaise on top to keep the avocado from browning and then the recipe says to mix the mayonnaise into the ...

Rebecca: No! why would you do that? You just-

Leila: And we thought it was abominable when The New York Times suggested that we put peas into guacamole.

Anna: They had no idea that there were so many worse options.

Rebecca: Yes. Like the peas-

Anna: [crosstalk 00:09:08] mayonnaise.

Rebecca: ... doesn't make any sense. But it doesn't horrify me on the same like deep level that the mayonnaise thing does.

Anna: It's not cosmically wrong in the same way-

Rebecca: Exactly.

Anna: ... that the mayonnaise suggestion is. And so I am fascinated by these kinds of foods and all the various ways that they augment women's labor in the kitchen and there's this really great, great [inaudible 00:09:41] ... Interesting, I guess push and pull between the things that are supposed to save you time but then you have to spend all the extra time making it look like real food, but you're supposed to use the manufactured food because that means you're embracing technological progress and bringing it into the home which is like a huge onus that's put on women in this period. They're sold this technological modernism in every aspect of what they're supposed to be ... their domain of the home. They're supposed to buy a vacuum cleaner. They're supposed to have a state of the art refrigerator. They're supposed to have all these kitchen appliances, and they're supposed to partake of these new foods but they're still being ... there's like retroactive tug of the lure of the past that fresh foods are sort of more moral, but they're fighting with this impulse to be more technological and buy like frozen foods or canned food or premade mayonnaise. Things like that.

Anna: So, I think that I like talking about the jello salad and the frosted sandwich loaf because everyone kind of has some experience with that. If nothing else, they've seen the pictures that go around especially in the holiday time on the Internet of like, look at this horrible bananas hollandaise or whatever. That's a particular bad one that comes up every year. But, I think that if we start picking apart these little oddities, these little pieces of American life and we apply different frameworks to them, like applying a technology framework to something like a jello salad, for one thing, the story then becomes about women which is what we're going for here and it puts women in a new historical light where we can understand them as not just being sort of swept along by history I guess, but actively kind of understanding these trends and like what counts as modern and what counts as technological and making decisions about that in the domain that they're sort of ... we think of them as restricted to.

Anna: So it's another way to kind of read back same agency into what women are doing and also to talk about spaces where women are participating in a culture of like scientific or technological practice in the home and in this domestic space. We'll put up a link to the article. It has some good recipe images that you will either like or be very disgusted by.

Rebecca: Or both.

Anna: Or both. But I am having a tree trimming party next week, and I'm making a jello salad. So I'll post a picture of it on the Lady Science Twitter when it's done.

Leila: Very nice. I also want to note just because I was looking very closely at this image while you were speaking that one of the mayonnaise frosted things is decorated with radishes that have been like sculpted to look like flowers. So I mean, the decorations on these get super elaborate and I mean that's why they're so fascinating.

Anna: I just love yeah ... There's like, you thought the frosting with the mayonnaise was bad. Like piping mayonnaise onto things with various cake decorating tips? That's a thing. Like put your star tip in your piping bag and then squirt some mayonnaise onto whatever. Anything really. You can put mayonnaise on anything. Sweet or savory.

Rebecca: It's so interesting on so many different levels but it's just such a good example of the performative nature of the mid-century housewife and the fact that so much stuff that is ... that seems on the surface to be labor saving wasn't actually labor saving. And there's a level of self-awareness and self-consciousness almost with these absurd things. Like piping mayonnaise on to something is just this level of absurdity that is I think in some ways appealing because you can imagine the women doing it, kind of knew hopefully how dumb it was, but they also knew that people would think it was cool. It's fun to imagine the women who were using this technology and how they thought about it.

Anna: And there's also ... I mentioned this in the article but one of the scholars that I was looking at for background on this also mentions an important point. When you're using cookbooks as a primary source is to remember that the rhetoric of the cookbook itself is prescriptive in a lot of ways, but you ... it doesn't account ... it can't account for what people actually did. So there is a limit to like the way that I've done this kind of analysis in that I can only say what the cookbooks and recipes are telling women to do and what that says about the sort of expectations of the larger culture they were living in. Because there are women in my family who will have no [inaudible 00:15:44] with any of that. At all. And they don't care about ... At the time, did not care about decorating their food or making it look a certain way. And there were certain women I'm sure who had no interest in technological food at all. So, I guess just as a historian, it's important to say what limits our sources have. But, also that you can ... I think it's really fun to think about these things this way and it can lead to a lot of different places.

Leila: So what I have for us to talk about today with net neutrality isn't historical, but I felt like it's an important conversation for us to have right now just because at this moment, it has a pretty uncertain future. On December 14th, the FCC will vote to roll back Title II of net neutrality and so that means that by the time this episode comes out, we'll either be rejoicing in the continuation of our neutral Internet or we'll be wondering why certain web pages won't load. A July 2017 poll showed that Americans, both Democrat and Republican overwhelmingly support net neutrality at 77%. Which might be the only thing that Republicans and Democrats are actually agreeing on right now. But despite the massively and popular effort to roll back net neutrality, FCC Chairman Ajit Pai, is pushing forward with rollback plans.

Leila: Just a quick summary of net neutral for listeners who might be unfamiliar with it. In 2015, the FCC reclassified Internet service providers, or ISPs as quote, "common carriers." Which basically means that ISPs were subject to regulation that prevents them from speeding up or slowing down Internet access, blocking content or websites that the ISP might not like or agree with and also prevents them from creating fast lanes that allows content favored by the ISP to load faster or to charge users extra for a priority access. So for example, back in 2007, Verizon Wireless wouldn't allow the abortion rights group, NARAL, to use its mobile network for messaging. So imagine how that could work if Verizon, as an ISP, didn't have to conform to net neutral protections. It could prevent users from visiting that site or just block it all together. And also, fun fact, Ajit Pai used to be a lawyer for Verizon. So there's a little bit of conflict of interest going on there.

Leila: And so today there's three things that I want to talk about which are generally overlooked a lot in discussions about net neutrality. And the first thing is how net neutrality intersects with class and race. And despite this being 2017, when the Internet should now be considered a utility and not a luxury, there are still millions of people without access and millions more without reliable or fast Internet access. And these issues of access fall predictable along class and racial lines, just about how everything else in the United States does. So in 2015, Pew Research Center found that people who make less than 30k a year are less likely to be connected. And a third of adults with less than a high school education do not use the Internet.

Leila: Hispanics and Black people are also less likely to have Internet access than white people. And then in a newer January 2017 study showed that both of these groups, people of color and low-income Americans were more reliant on their smartphones for Internet access than a broadband connection. So fast forward a little bit to June 2017 and a new report by Wireless Broadband Alliance found that 23 percent of Americans living in urban areas and 28 percent of Americans in rural areas, either don't have access to the Internet or they can't afford it.

Leila: And these statistics aside, there are still areas all over. So urban, suburban whatever that only get served by one ISP. So people in those areas already have no choice in who they buy their Internet access from. And so this just goes to show that even with net neutrality regulations in place, systemic social barriers of race and class create disparities between who can afford reliable Internet and who can't. And so without these protections that net neutrality affords, these disparities will be exacerbated even more. And one of the big things that I see this effecting is job opportunities. So, I don't know about you guys, but the last time that I filled out an application, a job application with pen and paper was probably over six years ago when I worked at Starbucks for a summer. So, job opportunities are mostly advertised online and most applications are also online. So more expensive or slow or unreliable Internet access will make it harder for already disadvantaged people to find and apply for jobs.

Leila: And several years ago when I was teaching at a community college, I also worked in the writing center there, and they had computers there for public use. And I don't know how many people from the surrounding community came in to use the computers just to apply for jobs. So this could put even more of a financial burden on public libraries and places like the community college that I worked at that also provide Internet to their communities. And it's not like the GOP hasn't already been trying to kill public libraries in higher education. So rolling back net neutrality is just, it's inimical to public good on multiple fronts. And the second point that I want to make is about labor and specifically women's labor and the Internet. One of the great things about the Internet is that it has really allowed for women's labor to become visible, either through social media or personal blogs and online publishing.

Leila: Women in other underrepresented communities have been able to find a place to cultivate a voice and sometimes even a career outside of traditional industries. Publishing for example has historically prioritized white male writers. Basically creating entire canons out of their work. And though this is changing very slowly, the publishing industry has typically been averse to accepting work by women, people of color, LGBT folks and others. And so the Internet has been a place where we could work around those closed systems and those gatekeeping tactics. Find other people like us and create new communities and cultivate new readerships online. So, net neutrality not only protects Internet users, but also content creators like us who rely on open networks to share their work. Lady Science for example is independent media and we are still small, but we have finally gotten to a point after three years where we can pay people for their work and the people that we mostly pay are women. And that's something that we're proud of.

Leila: We exist solely online, so it would be a big financial strain for us if we had to pay for priority access from an ISP just so that we could post content to our website, or run our social media accounts. So, money that should go towards paying women for their labor would go to paying an ISP. My last point about this is that I'm sure everyone has noticed unless they have had their head in the sand for the last couple of months is that right now our country is undergoing a really, really long overdue reckoning of male violence and sexual predation. And the media has undoubtedly played a major role in making that happen. And not just through media outlets, newspapers and magazines and things like that, but also people being able to share these stories online like with the MeToo hashtag on Twitter. And so this is the time when we need even more women's voices amplified and prioritized, not silenced.

Leila: Just because an ISP can be bought. So net neutrality intersects with class and race and gender and so many other issues and I can't stress enough how important it is that feminists get behind supporting net neutrality. Not only does it kind of protect the work that feminists do online, but it also it intersects with a lot of the issues that feminists are supposed to care about.

Rebecca: One of the things I want to sort of highlight that you mentioned that I think is important and that we forget in so many discussions of the Internet and by we, I mean like middle-class educated people who have Internet at home. Is that it's easy to lose track of how most people access the Internet. Like I feel like this comes up in discussions of public libraries and that there's a lot of people who access the Internet via the public library and a lot of the people that are making regulations about both the Internet and libraries don't realize that. There are just so many ... Yeah, intersectional issues that are buried in discussions of the Internet that don't always get highlighted and this is a better place where that's the case. I'm thinking about how most people actually use the Internet and what they use it for is so important.

Anna: And the point that you brought up about applying for jobs, I think is a really important thing to mention because quite apart from the difficulty of motivating people who already use the Internet all the time to do anything about this is we still are fighting people who think that the Internet is not real life and that you should have to pay for your Netflix or whatever. And who seem completely incapable of understanding that it is impossible, almost nearly impossible to live in a developed country and not have access to the Internet and it's something that argument that gets trotted out about welfare all the time. How could the government be paying you money if you have an iPhone? Or this idea that like, well, I saw a homeless person who had a cellphone. So they can't be doing that bad.

Rebecca: It's because if they're going to own one piece of modern technology, it being a smartphone is actually a really logical thing to do.

Anna: Absolutely.

Rebecca: Before you own a TV or a laptop or a car, owning a smartphone makes sense. And it's cheaper than all of those things.

Anna: And it's like having access to the Internet even for basic things like I was just thinking like maybe you live on the other side of town and you need to get to a food pantry and it takes you a long time to get across town and you need to plan and know what the hours of the food pantry are. And sometimes those places won't even have a phone that you can call. And so being able to have access to that information is hugely important. And I just ... I'm so incredibly fed up with this idea that the Internet isn't real life when so many of us rely on it for the most basic needs. Not to mention the people who work solely on the Internet, like us.

Leila: Yeah. Yeah, exactly. Well, and like there was a 2014 article that Bitch Magazine put out when this was coming up the first time around. And one of the points that they make in there is how net neutrality is really important for people to be connected to just what's going on in the world and I can't remember what the exact statistic was but like that the majority of Americans get their news and information through social networks by following those organizations on Facebook or Twitter that most people aren't sitting down and watching CNN or heaven forbid, Fox News, to be informed. That they're getting this on their own through the Internet, and seeking those things out through the Internet. And that when we block off those opportunities, that we're disenfranchising people from knowing about the world that they live in.

Anna: There's also this idea that I think is related to these arguments that always seem to come from like older people or just, I don't know. People who have a retrograde sensibility about the world that like ... that because the Internet is relatively new and because it provides things that we didn't have access to before that they are unspeakable luxuries that we're not entitled to. That, well back in my day, we had to use a dictionary to know what words mean, or what ... that's the kind of obnoxious example. But that either you're not entitled to them or you should have to pay for these luxuries like being able to Google for things or being able to watch TV on the Internet, just because the people making the arguments didn't have access to those things in the past and it's like ... especially in the United States it's such a weird argument to make in a country that spends so much of its time patting itself on the back for its technological progress. And it's just more proof that our politics are so ill equipped to deal with the technological progress that we appear to be capable of. Because we still think that it doesn't belong to everybody.

Leila: Yeah. And like these technology and all of this stuff is so intricately connected to the way we think about American progress and so what does it really mean when we're connecting America and progress but at the same time, disenfranchising large portions of its population to this progress. Like, progress for who? First of all. And can we call that progress when these systems that we've built disenfranchise most of its population? Or I guess not in this case, most, but a large majority.

Anna: Well, and that's the essential question is like who is the progress for? And it's for whoever can afford it. Because the death of net neutrality doesn't mean anything to you if money in general doesn't mean anything to you because you can pay for to open your throttle on all of your services all the way and so your Internet will look neutral anyway because the money isn't an issue for you. And the money issue like as it stratifies according to all of these categories of difference and disenfranchisement that we deal with in the rest of our political lives. And so the people who like you said, will be hurt most by this are the people who are always hurt most by American politics and it's just more piling on.

Rebecca: Well maybe if we are very lucky by the time this comes out, net neutrality will live to fight another day. Though, I don't think that this conversation will stop being as relevant because if we also don't have a permanent solution for this. So.

Leila: Yeah. And that's a big problem is that we don't have a permanent solution for this and because our politicians are so, they lack so much foresight and so much understanding of what the Internet is as a concept even that we can't have permanent solutions to this if our politicians aren't even taking the time to understand it.

Rebecca: We are now going back to the history time, so we've been talking about modern technology and now it's history times again.

Anna: History times.

Rebecca: It's 1947 in California. Southern California. My grandfather, David Hill was a young engineer hired by the Northrop Corporation to work on a new military project at the Edwards Air Force Base out in the Mojave Desert. Side note to all of this, at the time, the Air Force base was actually called Muroc. It was renamed Edwards just a little while later, so and that's what it's known as today. So that's just want I'm going to call it. Don't at me aerospace nerds. You know what I'm talking about.

Anna: I'll just delete that tweet I was going...

Rebecca: So, anyway, my grandfather is married to my grandmother who's name is Eileen and at the time in 1947, I think she would have been pregnant with my uncle and my mom wasn't born yet. So this is actually a pretty exciting time to be an aerospace engineer like my grandfather was. Chuck Yeager had just broken the sound barrier at Edwards Air Force Base, like the year before and a number of Air Force engineers and doctors and other scientists are investigating just how much gravitational force the body can endure if they were to send it out on a plane going really, really fast. Because it turns out that you can break the sound barrier and not die. So maybe you can go fast for other reasons like who knows? Going into space someday.

Rebecca: So, to do this, my grandfather and other engineers on this project, they built this sled and they attached some rocket bottles to it. And they hook up some sensors and they shoot ... they put a person on it, eventually and they shoot them down this track that was originally used I think to test V-2 rockets during World War II if I remember correctly. They start out with doing this with dummies but soon the main person doing this is, riding on the sled is this guy, an air force doctor named John Stapp who was kind of the head of this project.

Rebecca: And is sometimes called the fastest man alive, or the fastest man to ever live because of how fast he would go down this sled on it and would have some pretty terrible like medical thing happen to him because of it. But that's a whole other tangent. So getting back to Murphy's law though, the family story goes, so one day someone screwed up the sensors. That someone was maybe my grandfather or possibly one of his assistants, and so the sled goes out and it comes back with no readings on it. So they don't know anything about what happened with this particular sled test. That day, there was another air force major around who's name was Edward Murphy. He's visiting the test site, and he gets really angry about the screw up. So, at some point in his frustration or John Stapp's frustration or another engineer, makes the comment whatever can't go wrong will go wrong.

Rebecca: There's obviously multiple versions of this story. Some people say that this ... some obviously different versions of this idea of Murphy's Law existed already but it's a fun goofy story that my family usually sums up by saying, "Grandpa invented Murphy's Law", or "Grandpa was responsible for Murphy's law." And all of the silliness aside, this is really kind of a story about how my grandfather was part of history. So he's just a humble engineer. He was just like one of like the normal guys but he knew some important people who were doing this like cool, cutting edge science. He literally had his hands on the technological guts of the early space race and Cold War science, and so the specifics of the story don't really matter. It's just this idea of saying, "Hey, he was at Edwards Air Force Base for all of this like cool, science history stuff was happening." So I think that has had a lot of power for my family and it's just like a fun, wacky cocktail party story to tell.

Anna: Yeah. The one in my family is that my grandmother was a riveter working at Boeing during the war, so she was Rosie the Riveter, and it's a way to sort of like pin your family history to the larger timeline in a way that feels ... it makes things feel significant in a way, I think, and places you in the stream of history in a way that I think is really satisfying.

Rebecca: Eileen Hill, I think, also had her hands in the technological guts of history, but my family doesn't have the same kind of tidy story to illustrate that. That, I think just says a lot about the way we talk about gender and technology in history, and our families and that's really got me thinking about this topic and writing a blog post for us. And so my grandma, she was a seamstress. Sewing was really something she was passionate about and loved. She sewed most of my mom's clothes growing up, which my mom always joked she hated at the time, though it sounds like really amazing now. She always wanted to like buy a dress at the department store, dammit!. And in the 1950s, my grandmother was ... professionally sewed bathing suits and later designed them as well and she worked for two different companies based in the Los Angeles garment district. The more famous of those was Rose Marie Reid, but then she also worked for a company called Tobi of California.

Rebecca: And I think both of those companies still exist in some form or another today, though the 50s and 60s were really like the height of their work. So, my family does talk about my grandma's career all the time. I've known about my grandma bathing suit designer for awhile and my grandma loved telling stories. I think that she probably is who I first heard the Murphy's law story from. And she has plenty of stories about her childhood and the Depression and various kinds of things that she did. But, it's like we don't have that sort of historical context, weightiness to her stories about her being a seamstress. And that's really despite the fact that she is working in this technological industry because she's making bathing suits. And this is a time in the 1950s when there were a lot of new stretchy fabrics that are coming out and ideas about what women should wear are changing. And so designers and seamstresses like my grandmother are really being tasked with engineering puzzles. Despite my pedigree, I don't know very much about sewing. I can sew a button, but that's about as far as I can go.

Rebecca: But it seems like if you stopped and think about it, constructing a bathing suit actually seems pretty complicated, because you've got this garment that is totally form fitting. It's got to be sized to support a wide array of body types and the fabrics they're using in the 50s were really just invented and new fabrics are coming out. New like kinds of fabrics are coming out all the time. So, you've really got to know a lot about how to engineer your materials. And so, in writing ... in the essay I wrote, I kind of come to the conclusion that my grandmother was a kind of engineer. She was an engineer. Why shouldn't we talk about her that way? And why shouldn't we talk about women like her that way? And why don't we talk about the fact that she was designing clothes at this pivotal moment for both fashion and in women's relationship to the workplace.

Leila: Yeah. And I think part of that is that you're grandfather is attached ... they're attaching him to a really big world event, right? That that history in and of itself weighs or is just more present in people's minds and in people's memories than say a fashion revolution. But it also, those are also gendered histories, right? Like military history, rocket history, those types of things are men's history. Fashion is, that's women's history. So there's kind of a lot of layers as to who we're attaching to what historical story, and then which one of those stories is more important.

Anna: So in true to story and fashion, I have a reading recommendation for people who are interested in this kind of ... the way that differently gendered kinds of technologies get attached to that longer timeline in history. There's a book about the development of the spacesuit that's written by a design historian named Nicholas de Monchaux and I'll put a link in the show notes to the book. I have to say, as a space historian, I have problems with the way this book is put together, but what he does do is talk about the way that the spacesuit was only made possible because of certain innovations in the lingerie industry and made by Playtex specifically, and materials that Playtex was developing for their lingerie products and techniques and stuff that were ported over into the design and manufacture of spacesuits.

Anna: And because of those innovations, that's part of the reason that spacesuits are soft instead of hard. So sometimes you'll see like prototypes that are made out of fiberglass or sometimes they're made out of aluminum. That they are hard shells. But the spacesuits that we used in the United States are soft and made out of multiple layers of innovative fabrics that were being used to make women's garments before.

Rebecca: I do want to say that one thing that I find also interesting and kind of frustrating about yeah, the way we talk about connections between spacesuits and women's garments and Playtex and all of that, which it's an awesome story, and it's fun to share that with people and it's totally worthy sharing. But there's always a little bit about that to me that it's like, what Playtex did was valuable only because it went and like was part of this super manly industry.

Anna: Yes. Like I've seen that book described as like recovering the origins of the spacesuit in technology of women's garments. But to me it seemed like there's plenty of fashion history that's been written about that but it's just not considered as glamorous as other kinds of history. So he wasn't recovering anything, really. He was just saying that we could think of it as something worth our time now because it was connected to spacesuits.

Rebecca: Right. Yeah. Yeah. And like I think the connection is really neat, but yeah, sometimes there is ... you hear that story enough and you start to wonder if like it's really about how these things don't matter until they're part of spacesuits and-

Anna: Yeah. Well, and literally it's like they don't matter, this material and technology doesn't matter until it's been transformed into a garment for men.

Rebecca: Exactly.

Leila: Well, I think that is as good of time as any to bring in our guest for today. Our guest is historian of technology and writer, Dr. Marie Hicks who is currently an assistant professor at the University of Wisconsin. Her research focuses on the history of computing, labor, technology and queer science and technology studies. She is also a Lady Science contributor. She wrote the foreword to our 2016 anthology and in January of this year, she published a book with MIT Press titled, Programmed Inequality: How Britain Discarded Women Technologists and Lost Its Edge in Computing in which she explores how Britain's computing industry, once top in the world after World War II, had diminished by the 1970s. Welcome to the podcast, Marie.

M. Hicks: Thank you so much for having me.

Leila: Yay.

Rebecca: Yay.

Leila: We have a very adult podcast.

Rebecca: Yep. We're [inaudible 00:46:18]. Definitely.

Leila: So, a question of origin that I like to ask people is how did you come to research gender and computing in British history?

M. Hicks: Well, there were a couple of different parts to that. I was a history major as an undergraduate ,and I always sort of thought I might like to go back to graduate school but I knew that would be a little bit of a hard slog. I knew jobs weren't plentiful and so I worked for awhile after I graduated from college. And I ended up actually working as a Unix systems administrator. And it was odd in that job. I was in my 20s then. So all of the young folks like me, we were all ... the gender imbalance was really stark. So for awhile, I was the only woman there. And our bosses, our older bosses were all women actually. And so we had these conversations about well why is there this seemingly backwards gender distribution? And our bosses would tell us stuff like, oh well, you know you don't really understand. History is not progressive. There used to be a lot more women around. And then that was sort of what got me interested in the germ of the story about what happened with that gendered labor flip.

M. Hicks: I knew it had happened in the United States and later on when I went back to grad school to try to figure out what was going on with this story, I thought about making it a comparative story for a little while, but the reason I didn't is because the history of technology and particularly the history of computing, it's really, really over studied in the US context. And that means that we lose a lot. We miss a lot of things when we're only looking at the US. So I decided to just kind of do a deeper dive into another national context that has a lot of interesting stuff going on in computer early on.

Rebecca: So another interesting thing that I learned from all of this is that in 1944, Britain led the world in computing. So can you explain a little bit about why they were so far ahead of other countries at that time?

M. Hicks: Sure. Well one of the points that I make in the early part of my book is that we really have to think about computers as war machines because that's what they start off as being. And that's why the UK is so ahead because they are getting the shit bombed out of them. And they need some way to try to survive this war. And the US has the relative luxury of going slower but the UK doesn't and it's in this context of aerial bombardment that they're trying to create the first electronic computers in order to break codes more quickly so that they can figure out more effectively how to fight and how to survive. And so that's the frame into which these first digital electronic programmable computers come. And they're designed by a guy named Tommy Flowers at the post office which was kind of like the place for cutting edge telecommunications and electronics research at that time. But they're put together, and they are trouble-shot and they're operated by women.

Anna: You describe in the book that by the 1970s, a really short period of time, just over 20 years, Britain had already fallen behind in computing and you argue that this was in part the result of the feminization of labor and gendered technocracy. So can you explain I guess the argument of your book and what you mean by that?

Leila: That's kind of a big question. Yeah.

M. Hicks: Sure. Yeah, I mean, I went in to the archives wanting to write a story about how the field of computing went from being seen as feminized work early on to being seen as male-identified and really male-dominated. So I just wanted to explain why this gendered labor shift had occurred and when I got in there, as often happens, when you get into the archives, you find out other stuff and so there was this thread that I kept pulling going through the archives about what was the effect actually of trying to get women out of the field once the government decided and once industry decided that essentially these jobs which had previously been seen as low skill and they had been perceived as rote and unintellectual. Well, these programming and computer operating jobs eventually began to be seen as actually very important because people started to understand the importance of computers.

M. Hicks: And the content of the work didn't change, but because how it was perceived changed, it led to this huge push to get women out of the field and to get men trained in the field. And what I found out which was kind of surprising but I guess in retrospect it shouldn't have been was as the British government is ramping up for all of this computerization, while they're pushing out all of the people who have the skills because they're women, and this leads to disastrous things on a national level. It essentially causes the British computing industry to implode. And that's why the UK goes from this very early strong lead in the war time period but also in the post-war period, to basically in the 60s, in the late 60s, just crumbling.

Leila: You do make a distinction between labor feminization and work that is just performed by women. And so I was wondering if you could kind of unpack that difference a little bit.

M. Hicks: Sure. Labor feminization means that the work is performed almost primarily or predominantly by women, but it also has this element of deskilling, right? Not always that it actually is deskilled, but that there is a perception of deskilling. Which allows things like wages to be depressed for instance. And so there are actually ... I mean there are a few fields where there's a majority of women doing the work like some sub-specialties in medicine, but we would never call those fields feminized because what feminization actually entails is essentially seeing workers as less valuable because they're women and because they're doing work that's seen as appropriate to women who are unfortunately still a lower status workforce. And so one of the things that I always talk about in my class when we talk about like labor feminization in either the Industrial Revolution or in the 20th century with what I study, is I bring out like some of the archival examples in the book and I show the students how when equal pay gets introduced into the British government, the women who are doing all of this machine work, they don't get equal pay.

M. Hicks: Because even though there are men's pay scales, the government says, "No look, this field is so feminized. Women have been doing it in such majority for so long, that's the market rate for the job now. So of course we're not going to raise your wages to the men's pay scales because we never use the men's pay scales." And so what that shows is how it depresses wages across the board because once that wage is set at that lower level, all the other jobs around it that are done by mixed gender workforces, they get tied to that rate and further more, if men come back into the field, that doesn't just automatically mean the wages go up. So, I just try to show how feminization is, obviously it's bad for women but it's bad for all workers. This is really an issue of labor and of class.

Leila: Yeah. There was a part in the book where it was like, well all these people are making a fuss about wanting equal pay. How are we going to deal with that? Oh, we'll just create an underclass of workers and put the women in there.

M. Hicks: Yeah. And exactly so, it was like a whole class of workers. In fact, the majority of women who worked in the civil service, they didn't get equal pay when equal pay came in because the majority of women were in these machine grade jobs.

Rebecca: So how did Britain as a country become so tied to the success and failure of the computer industry?

M. Hicks: So the argument I'm making in my book isn't necessarily that the failure of the British computing industry dragged everything else down. The UK was sliding into second-rate world power status for a lot of reasons in this period. Essentially they had been an imperial power and then they were losing their empire because around the globe, people that they had colonized and oppressed were saying "no more." And so that was ending and the UK was trying to basically try to figure out how to have a second act as an empire. They were looking for a lever to make them neo-imperial power, if you will. So instead of going around the world and using guns and boats and whatever else to try to dominate, they thought, well we can use computing. We can use technological expertise to compete globally, and not just compete but actually to dominate globally. Maybe dominate areas where we had previously dominated in other ways militarily. We can still dominate economically through technology.

M. Hicks: And so this is why the government thought that computer was so important and was so obsessed with it. And that's why actually in a paradoxical way, that's why they made these really bad mistakes with their labor force, because they were so invested in computing. And so that's basically why they saw it as so important. And it's certainly when things didn't go well, and the computing industry imploded, a lot of people lost their jobs. It dragged down the gross domestic product. It hurt their balance of trade. We don't have Silicon Valley coming out of the UK. Depending on your perspective, that might be a good thing or a bad thing. But they lost that engine of their economy.

M. Hicks: And I mean, if I feel like we have a lot of that stuff going on even today and certainly going on in the US context and when we talk about like falling behind other countries or falling behind China technologically. It's all sort of part of kind of a cold war in a sense and that's one of the reasons that I do think it's so important to remember that computing technology not just comes out of the war but was specifically designed for warfare and was specifically designed for cold warfaring throughout the period after World War II. I think a lot of things that are going on now make a lot more sense when we think about it in that way, instead of having this idea of like, oh the computers we use are descended from the personal computer. 1970s, 1980s. It's much harder, I think to understand cloud computing and what it does in our economy if we think of personal computing as the nearest cousin of the computers we use today. It's really not.

Leila: Yeah. And I think because you take such a longer view of the history of this, by starting in the 40s, that it gives a much better understanding of that this was kind of ... that this was a process that was ongoing, and so if you start like in the 60s, or you're starting in the middle of the story. You're not really getting that long view that provides for that ... the type of long analysis that you do over time.

Anna: So, once in awhile old advertisements for computing sort of make the rounds on social media and there's usually a young white woman next to a machine of some type and then usually there's some kind of boring commentary like, see, women have always been programmers! But you spend quite a bit more time with these images and analyzing them, and you talk about how it's a little more complex than women just being there. And so, I wonder if you could talk about why showing these gendered bodies of workers was so integral to the companies making these advertisements.

M. Hicks: Sure. Yeah. And I'll just say too right up front, in terms of like my archival practice, the images were some of the first ways into this story, to actually seeing the women. Because I had to do a lot of like really deep dives into written archives in order to figure out that women were even there. And I had to learn a lot of tricks and sort of what categories were used to refer to women that weren't ... used to refer to men. And that took months of research to actually get to the point where I could find women that way. But the first place I saw them was in all the images and some of these were advertisements and some of them sort of seemed like advertisements but they were the actual workers who were sitting in front of the machines.

M. Hicks: And I would try to talk about this early on with other people who were actually even in my field in some cases and they would say, "Oh yeah, well the women were just there as pretty faces. They were just brought in to stand next to the machine." And that was actually not the case at all and I had to go through quite a lot of trouble to prove that that wasn't the case. And I think it's interesting now that I don't think we have that impression quite as much, but I think that's been a relatively recent shift. And the other thing about these ads or these publicity photos which are actually using real workers was that they weren't just using women as pretty faces, and they weren't just using women to show, oh look, this machine is simple to operate. They were using women because women were a stand in for essentially cheap, non-unionized labor. Labor that was going to have a high turnover. Wasn't going to need a whole lot of training time.

M. Hicks: And wasn't going to be trouble for managers. Again and again in the history of technology and political history we see how machines are often used, automation is often used not necessarily to make things more efficient but so that management can get more control over a process or a labor force. And that's exactly what was happening with computers, but as the machines rise in status, there's this interesting kind of split between how the machines are being advertised: "Oh you can use women to run them," and how they're actually being staffed, because the tricky thing about these ads is by showing women as essentially less valuable workers, they undercut the idea that women actually can do these more important computing jobs. And so when the government and when industry start to see these jobs as more important, they actually end up going to more expensive workers who they think are going to do the jobs better than the women who have been pitched in the ads.

Anna: I think that's a really fascinating, that these images are like, they're advertising to managers of like if you incorporate computing into your business, then you can have this labor force that's easily controllable.

Leila: And in the book, you call it the managerial gaze.

Rebecca: Ooh, that's good.

Leila: Yeah. And there's like that one image of like two men and they're facing ... you just see them from the back. You don't see their faces really. And they're like watching this woman working a machine. And it's like totally creepy and I know that visual culture people, especially feminists, visual theorists would have just like a field day with that image. But, casting it as a specific type of gaze really adds that dimension to the analysis.

Anna: So I want to ask about a different kind of gaze. You talk about the managerial gaze. But there's also an imperial gaze in advertisements for computers in the Middle East and Africa and India, and I just wondered if you could talk about especially connected to our discussion of computing as maybe a substitute or a next step or a re-up of empire for Britain.

M. Hicks: Yeah. I mean, in a similar sort of way that the managerial gaze is kind of gaining power over white women by putting white British women in these ads and arranging their labor in certain ways, things like that are happening with advertisements that are meant to be seen by government, leaders, and industry leaders in other countries. So in the early period, there are a lot of incredibly racist, imperialist ads that talk about how British computing is going to come in and civilize the country. And they're talking about this technology as a civilizing force and all this. And later on, one of the things that you see happening also more and more is this exoticization of women of color bodies in advertisements or not even in advertisements, just when pictures are taken of them working in their job in the machine room.

M. Hicks: I remember in the book there's this one picture of a woman in Ghana working on a British computing installation and the caption says something like, "Hot Stuff." And it's incredibly insulting and honestly it wouldn't have been that same sort of language being used with white women quite as disrespectfully. But because there was this idea that well, these women are essentially not even second class citizens, but third or fourth or whatever and there had just been this tradition of imperialist disrespect that permeates its way through into all of these ads as well.

Leila: So when I was reading your book, it was really difficult to avoid drawing connections between what you show in your book and what is happening in tech fields today. And I don't necessarily think that a historical argument needs to be relevant today to be interesting or important, but it is difficult to not make those connections with your book. So I am wondering where do you see some of these problems and inequalities playing out now?

M. Hicks: Sure. Yeah. I mean the thing is, fields professionalize and then they lose status. This is an ongoing process, and there's always a push to take power away from workers, even if those workers are white collar and relatively high in status. You don't have to really go any further than like walking through a major company today, and if you're old enough to have walked through a similar company 10 years ago, you'll see for instance just how much less space programmers have to even just sit in and do their jobs and how they're packed in tighter and tighter. So even though they're incredibly well paid, they're subject to the same sort of forces that we're all subject to. Where, essentially, if our labor can be undervalued, it will be.

M. Hicks: And that's just kind of like a little minor example. The space issue. But a lot of my friends who worked in RTP. I went to Duke University for my graduate degree and so Research Triangle Park is right around there. So a lot of my friends then who are still my friends, they were tech workers and they were H1B visa tech workers. And I would see them consistently undervalued and abused by the companies that they worked for because they were tied to these special visas. The visa was supposed to be a thing that they got because they had special skills, right? That you couldn't find here in the United States. But in fact what you would see happen again and again is that white people, especially white men who were doing the same jobs, would be treated far better. Would be paid far better because folks who were here on H1B visas, they couldn't move around. They couldn't leave a bad job situation as easily because the visa is tied to the job and to the company to a certain extent.

M. Hicks: And I think it's important, actually, to remember that when we hear like Silicon Valley talking about like, oh, we have a shortage of labor and we need people with these skills. Because, honestly, they're bringing in people who yes, have the skills, but they're bringing in people like that so that they can exert more control and pay them less. It's not a matter of there not being enough people stateside to do these jobs. It's once again, a move to try to undervalue workers and I think that when I used to talk about that maybe like even a couple of years ago, people thought that that was an overstatement but now we're seeing more and more examples of how that's exactly what's going on.

Rebecca: Yeah. I feel like I read an article recently-ish that was even about programmers that get paid well, but because they're on contract, they have no job security and they sort of jump from Silicon Valley, company to company doing different kinds of thing as their contracts run out and so it's like as even ... I think it was, the article was something about like even programmers are suffering because of the gig economy and the way that kind of mindset is even entering what we think of is very professionalized, high-skill, white collar jobs.

M. Hicks: Yeah. Yeah. I remember maybe a little under a decade now ago, I saw an article, or actually my partner saw this article and it was like a ranking of the best jobs you could have in terms of job security and pay and stuff like that. And number one was computer programmer. That happens to be what my partner does. And number two was university professor. And we both had a real good laugh about that because I was adjuncting, struggling, struggling to survive at that point and my partner also understood sort of which way the wind was blowing. And like I said, that was less than a decade ago and it just goes to show how quickly things can change. Like now, obviously adjuncts have it far worse than contract workers in Silicon Valley, but you can see it's on the same sort of spectrum of labor that's being made more and more contingent and being made sort of more interchangeable in ways that serve companies, serve corporate universities far more than they serve either workers or in fact the productivity of our economy.

Leila: That's a great place for us to wrap up. So, we will include a link to Dr. Hick's website in the show notes that you can read more about Programmed Inequality and just keep up with the exciting research that she is doing there. So thanks again for chatting with us. It was a real pleasure to have you.

Anna: At the end of every podcast, hosts will unburden themselves with one thing in the news, their work or the world in general that's just annoying the crap out of them. So this is one annoying thing.

Leila: So this month, I am annoyed with ... and this is kind of keeping with the technology theme. A man invented an app to apply to women's pictures to show what they look like without makeup. And it's called MakeApp and it gives you five free photos before you have to start paying $0.99 to reveal the lies of as many women online as you would like and how much your heart desires.

Rebecca: This thing makes me want to vomit.

Leila: It really does. So, first of all, it is ridiculous concept that men just feel that women are lying to them or something by wearing makeup. That we're deceiving men into thinking we're more attractive than we are because we wear makeup. And there's always been this idea that women in their profile pictures are lying about how attractive they are by the way that they pose themselves in the selfies to make themself thinner than they are. Or lightning their skin, darkening their skin to look like they have a tan. Boosting up their boobs a little bit. And then like situating the camera in such a way. So there's already been like all of this criticism about how women try their hardest to make themselves look more attractive than they are in their profile pictures online. Because men don't do that, right? Men don't try to accentuate the things that they think are more attractive about them but that this does disproportionately apply to women. Just deceiving people into thinking they're more attractive than they are.

Anna: That's the thing about this app that makes me crazy most is that most of the time, men can't even tell when we're wearing makeup and they just think that our faces look like that anyways. So what the ...

Leila: Yeah. And it's ridiculous. And it's still just another filter that you're applying to someone's face. Like this isn't more ... it doesn't make her look more authentic or anything. It's still just as fake as everything else that you're accusing this woman of doing.

Anna: I feel like this is related to the CSI photo enhance myth that we've been fed about what technology is capable of that we can just like, "computer, show me her real face" and somehow a computer can do that.

Leila: Yeah. Exactly. I saw a Tweet going around with this that was like, we were promised flying cars. Instead we get an app that shows what women look like without makeup. It's like, wow is this truly the future that we wanted?

Rebecca: No.

Leila: Anyway, I don't have anything like intellectual to say about that. It's just something that is ...

Rebecca: Yes.

Anna: Ugh. It's just also like to this man who built this app, who obviously has some skills if he's an app developer, I guess, what are you doing with your time? And who hurt you?

Rebecca: And like, and this is actually going to connect to my annoying thing. But yeah, you were saying, it goes to this whole really terrible idea that women lie and that women are inscrutable in some way, and that women have all of these tricks and games so that you can't figure out what's going on with them. So, we have to have this app that takes care of that. Which is like not disconnected frankly from the both the run of sexual harassment revelations that have happened recently, and abuse revelations, and the reactions to them. And the idea that is really insidious and part of rape culture that well you can't just, you can't ... women never say what they really mean, so you never really know. Which is terrible and I think connects to ... yeah. It's all part of that same terrible soup.

Rebecca: And also it comes to this thing that I have noticed happen to me a couple of times since Harvey Weinstein and all the other allegations that are coming out of harassment charges against powerful men where various people have like in a half joking but not really sort of way said to me, "You know, I would give you a compliment, but I hear that could be bad now. I don't want to say it wrong." And it just ... [inaudible 01:17:48]

Leila: Oh my [crosstalk 01:17:52].

Rebecca: If you were genuinely concerned, you could just not say anything first of all. Second of all, you are like a human being in the world. You know the difference between ... you should know the difference between like what makes someone feel gross and what is just, hey you look nice today and we're two human beings like who interact on a regular basis and can you know, have polite conversation with each other.

Leila: Yeah. And I hate that like, I've had this conversation with two men in my life since all of this stuff with, you starting with Harvey Weinstein and everything, then Louis C.K. and all that came out. Is like this like hand wringing over about can I ... what if I've made a woman uncomfortable by giving her a hug or something? And what if she is going to accuse me of sexual harassment. And I was like, "First of all, no one is accusing of any of these men from a hug."

Rebecca: Right!

Leila: These men are like masturbating in front of them. So if you somehow have done that, these cases are in no way comparable.

Rebecca: Yeah.

Anna: And you know what? I don't have any patience for men who supposedly can't figure out all of the inscrutable womanly sorcery we do with like what we consider appropriate or not, because I know exactly when something is friendly, and when it shifts over into being predatory. And that is a very finely honed sense that I have, like a rabbit that I developed over my whole entire life and I've devoted so much hard drive space to honing that instinct and knowing and keeping myself safe. I don't have patience for men who can't just fucking figure out a basic social signals. No. You have to figure it out. You have to figure out how to be a person in the world, because we have to navigate the world in a way that is ... It's like we have to read the Matrix in code and you can't even figure out how to do it looking at it when it's all loaded up. It's just ... Sorry.

Leila: But I also want to note that just citing that the only way you can't sexual harass someone is to not be around a woman-

Rebecca: Oh yeah.

Leila: ... and so therefore you start to exclude them from your circles and your business meetings and your business dinners and your business drinks. Like that is also the opposite end of the spectrum. Don't do that.

Anna: Yeah. The Mike Pence model of being an adult is not what we're looking for either. It's up to men to figure out where to strike that balance. Just so tired of having to teach them how to be people. Okay so, to close this out of our episode that has been about technology and in large part, I think, about labor and those two things are very intimately connected, I just wanted to relate a disappointed conversation I had with my mother.

Leila: Does she listen to the podcast?

Anna: She does not, because she doesn't know what a podcast is and I'm not going to teach her. So ... I've been kind of ... I've been trying to be a little more like forward with my political beliefs around my family because it has come to my attention that they don't know what they are, which I always thought that I was the shrieking communist of the family, but apparently I have not been loud enough. So I was talking to my mom about, my dad works for a company that has a union. We've always had this thing in my family about how my dad's a company man. He's not a union man. I thought people in my parent's generation like working class, were pro-union generally. Just goes to show no accounting for anything anymore.

Anna: But they're not pro-union. They're like company people. And I keep trying to tell my mom, his company is awful to him and the only reason that it hasn't been worse is because they have a union. And they have been on strike like once in like 25 years. Been pretty good so far. But they're still firmly convinced that their loyalty lies with the company and that the union ... all they do is get people's jobs back who were stealing from the company. So, we're talking about this and my mom says something about how even though the company is really bad to him, it gives you this sense of pride to do a good job in an adverse environment. And I said something to the effect of that's what the man tells you to keep you under his thumb.

Rebecca: Yeah.

Anna: And she said, "You don't really believe that. You can't believe that because you are a hard worker." So first of all, the fact that my mom doesn't know that I'm like fiercely pro-union, aside, the idea that you can't ... it just reveals so much about what she thinks a union is for, is to protect lazy people. That I should have no interest in unionization because I want to work hard. Only people who don't work hard need a union. And so I've been seeing a lot of stuff on Twitter lately because the LA Times is unionizing and Fox is unionizing or trying to, and there are really dumb, anti-union sentiment floating around. And this idea that unions are for lazy people is something that I have seen a couple times online with regard to writers especially. Written by another writer, by the way, who quote on quote, "supports unions but not this one". Because it's the ethical center left thing to support a union but as soon as it comes anywhere near you, you just start shrieking about how it makes people lazy.

Anna: So, I'm not really sure where I'm going with this other than the fact that it's very disheartening to me how the status of organized labor, like its social and cultural status, has basically plummeted in the last 30 years, and that it seems like there's a very large swath of United States who thinks the way my mom does, that unions get people their job back when they do bad things at work.

Leila: Like this country does not do a good job or a job at all of teaching labor history as a part of American history in general. Like that is not ... I mean, if you're lucky enough to be in a school district that actually teaches civil rights, labor is left out of that entirely. And I don't remember ever getting it in college either, unless I took a class that was specifically geared that way. But like ...

Rebecca: And that has...also, not teaching that history has real consequences now because when we talk about today, it's often in contrast to like mid-20th century working-class and middle-class prosperity and you can't talk about that contrast without talking about labor history. And yet we do.

Leila: Well I think that's a good place for us to wrap up. We had some good rants today. Good job guys.

Rebecca: Yeah.

Anna: We are the little [inaudible 01:25:46] I think between me and Mar. We took care of it.

Leila: Yeah. So listeners, if you like our episode today, head right on over to iTunes and leave us a rating and a review so that others can find us and listen also. Questions about any of the segments today, Tweet us @ladyxscience or, #ladyscipod. To sign up for our monthly newsletter, read monthly issues, pitch us an idea for an article and more, visit ladyscience.com. We are an independent magazine and we depend on the support from our readers and listeners. You can support us through a monthly donation with Patreon or through a one-time donation. Just visit ladyscience.com/donate. And until next time, you can find us on Facebook at @ladysciencemag, and on Twitter at @ladyxscience.