Episode 37: The Decline of the Brewster

Hosts: Anna Reser, Leila McNeill, and Rebecca Ortenberg

Producer: Leila McNeill

Music: Fall asleep under a million stars by Springtide

Rate. Review. Subscribe.

In this episode, the hosts discuss the long history of women in the world of beer and brewing. From ancient godesses to medieval brewsters and alewives, women dominated brewing until changing economies and men gradually pushed them out.

SHOW NOTES

Flora Unveiled: The Discovery & Denial of Sex in Plants by Lincoln Taiz and Lee Taiz

Fermenting Revolution: How to Drink Beer and Save the World by Christopher M. O’Brien

The Geography of Beer: Regions, Environment, and Societies edited by Mark Patterson, Nancy Hoalst-Pullen

“Medicinal beer? New study shows maybe the ancient Nubians were onto something” The Mercury News

“Beer in Ancient Egypt” by Joshua J. Mark

Ale, Beer, and Brewsters in England: Women's Work in a Changing World, 1300-1600 by Judith M. Bennett

“Women and Beer: A Forgotten Pairing” National Women’s History Museum

“Female Brewers in Holland and England” By Marjolein van Dekken

“‘Ale for an Englishman is a natural drink’: the Dutch and the origins of beer brewing in late medieval England” by Milan Pajic

TRANSCRIPT

Transcription by Julia Pass

Rebecca: This doesn't have to do with the podcast at all, but the thing I find hilarious about Thomas Jefferson is that it's not that he was that much more shitty than many of the other Founding Fathers, but he wrote down every shitty thought he had. George Washington knew when to keep his mouth shut.

Rebecca: Welcome to Episode 37 of the Lady Science Podcast. This podcast is a monthly deep dive on topics centered on women and gender in the history and popular culture of science. I'm Rebecca Ortenberg, Lady Science's managing editor.

Anna: I'm Anna Reser, co-founder and co-editor-in-chief of Lady Science.

Leila: And I'm Leila McNeill, co-founder and co-editor-in-chief of Lady Science.

Rebecca: And today we're goin' to be talking about women in the history of beer brewing. Yay drinking. That seems appropriate to the era we're living in. Hurray beer! Hurray beer!

Rebecca: Yeah. When it comes to beer, many of us conjure up images of white dudes with beards wearing flannel standing in a taproom, or at least that's what all the Instagram accounts of breweries in, I think, all of our areas show. And as I was saying before we started the podcast, that's certainly unfortunately my representation as someone who lived in Portland, Oregon, in the early aughts. Love you, Portland. You're a stereotype of yourself sometimes.

Rebecca: Anyway, converse to all of that, though, historically across time and place women have consistently been associated with beer in the images of goddesses, and women have been responsible for the labor of brewing.

Leila: Let's start there with the oldest known recipe for beer, which comes from an ancient, 4,000-year-old Sumerian hymn. The hymn glorifies the goddess Ninkasi, who was believed to preside over the beer making industry, and it goes like this: "Ninkasi, it is you who handle the dough with a big shovel, mixing it in a pit, the beer bread with sweet aromatics. It is you who bake the beer bread in the big oven and put in order the piles of hulled grain. It is you who water the earth-covered malt. The noble dogs guard it even from the potentates.

Leila: "It is you who soak the malt in a jar. The waves rise. The waves fall. It is you who spread the cooked mash on large reed mats. Coolness overcomes. It is you who hold with both hands the great sweet wort, brewing it with honey and wine. You place the fermenting vat, which makes a pleasant sound, appropriately on top of a large collector vat. It is you who pour the filtered beer of the collector vat. It is like the onrush of the Tigris and the Euphrates."

Anna: I love that.

Leila: Yeah. It's super cool. This hymn gives us solid evidence of what the actual brewing process was like in ancient Sumeria and shows us that their beer culture was women-centric. And that's one of the things I really like about this, is that it's a hymn but it's also an oral way of handing down the method of making the beer. And Sumerian women were also responsible for brewing the beer for religious ceremonies and daily consumption.

Leila: But also keep in mind that this was typically low alcohol content beer, not the 10% or 12% ABV you can get today and which you definitely should not be consuming daily.

Anna: That's a New Year's Eve beer, not a lunchtime beer.

Rebecca: It feels worth noting that, as I'm sure many beer drinkers out there probably clocked, that Ninkasi is one of those beers that you probably associate with dudes with beards.

Leila: Oh, is it? Is that a name of a beer?

Rebecca: Yeah. Ninkasi's the name of a beer. I don't really know a lot about it, but it's one of those that I feel like I see at a good taproom.

Anna: "Ninkasi Brewing Company is the nation's 38th largest independent craft beer." That's so random. Weird flex, but okay.

Anna: Ancient Sumeria wasn't the only place that associated women and beer. We go a little farther north. We find that in ancient Finland people also honored a woman goddess of beer. So according to myth, three women named Osmotar, Kapo, Kalevatar—I know that's terrible. I don't know any Finnish.

Leila: That's okay. Just keep going.

Anna: These women created beer while preparing for wedding festivities. At first the women couldn't make the beer foam, but then the Kalevatar combined bear saliva with honey, and that created the foamy beer. This story is recorded in the Kalevala, which is an epic poem compiled from oral folklore and mythology that recounts the creation of the Earth.

Anna: According to Christopher O'Brien in the book Fermenting Revolution, the story of the three sisters and the origin of beer is given twice the narrative space than that given to the creation of the world itself. And you know what? I agree with this. Clearly this shows the importance of beer, obviously, to ancient Finnish society but to human society in general and points out, again, that women are at the center of this story.

Rebecca: Heading back down out of the frozen Arctic to ancient Egypt—Finland is a very cold place, okay?

Leila: It is very cold.

Rebecca: Anyway, in ancient Egypt, the goddess Tenenet presided over brewers who were also women. And women, in fact, were the first brewers in Egypt. Egyptologist Helen Strudwick has said that, quote, "Both brewing and baking were activities undertaken by women, and numerous statuettes found in tombs show women grinding grain in mills or sifting the resulting flour." End quote.

Rebecca: And this is just interesting to me because we still today associate baking with women, and of course brewing and baking go together because they both involve grain. It is just interesting how one of these things has remained something that is feminized and the other one has gone off in this masculinized direction.

Rebecca: In any case, beer was given out as compensation for physical labor in ancient Egypt. Laborers received a ration of eight pints a day. Don't get too excited. Like we mentioned earlier, people weren't getting drunk from this beer. It usually only contained three to four percent alcohol and was really consumed for nutritional purposes. There were higher alcohol content beers, but they were usually reserved for festivals and religious ceremonies.

Rebecca: What's more, beer was a key ingredient for many Egyptian medicines. In ancient medical texts, we can find over 100 medicinal recipes that use beer. And anthropologists have found that in Nubia, which is located in present-day Sudan, beer was used as an antibiotic to treat a variety of infections. In the 2,000-year-old bones excavated from the region, they found evidence of high concentrations of the antibiotic tetracycline. That suggests that the Nubian people regularly consumed beer from vats in which the tetracycline thrived and that Nubian brewers had perfected the technique of brewing antibiotic beer.

Rebecca: Joshua Mark writes that while beer was first brewed in the home by women, it was ultimately taken over by men when it became a state-funded industry, which I'm sure will sound familiar to many of you. And we'll hear more about how that happened in this episode.

Leila: And we know that women remained dominant in brewing and ale into the Middle Ages in Europe, West Africa, and other places around the world. In Ale, Beer, and Brewsters in England, historian Judith Bennett finds that as of 1300, women were doing most of the brewing in Europe. And in England they were called brewsters, which was distinct from the male brewer.

Leila: Bennett writes, quote, "Brewster once had a clear and unequivocal meaning: a female brewer. By 1500, however, the neat gender distinction of brewer and brewster was fading away. Over time brewer won out as a term for both sexes and brewster survived only in limited uses. In losing brewster, we have lost sight of a critical part of history."

End quote. So in this episode let's take a look at what happened, how brewer not only replaced brewster in name but also in occupation and industry.

Anna: At the beginning of the 1300s, the brewing trade did not look anything like what we have today. Most ale brewing was done in the home by women, to be consumed daily by their own families. For England and much of Europe and later in the American colonies, ale was a substitute for water because water was often unsanitary. It was consumed by adults and children alike, and both poor and elite households brewed their own ales on a regular basis. And this is what is called domestic brewing.

Anna: So people who sold their ale for profit break down into three categories, and women dominated all three of these categories. So that would be commercial brewers, occasional brewers, and by-industrial brewers. A commercial brewer brewed mainly for profit, whereas occasional and by-industrial brewers brewed for their own consumption and then sometimes turned a profit but not very often. So for example, sometimes women would sell their ales to friends and neighbors in small amounts, often whatever was left over from their family before it spoiled, or they would supply their manor houses with their ale.

Anna: Some people made their homes into makeshift taverns where their neighbors could buy and drink the family ales. Establishments that only sold and did not brew their own ale were pretty rare during this time, and though most brewers were married women, single women and widows also brewed and turned a profit making beer. But this was much more rare, for single men or widowers to brew on their own without a woman involved, and that's because brewing was women's work.

Rebecca: So to understand this gender breakdown in brewing, Bennett relies mostly on public records related to the regulation on price and sale of ale and the grain that was used to make the ale. So these documents exclusively reference female brewsters during and before the 14th century. But despite the pervasiveness of brewing and the importance of ale on all levels of society, it wasn't a particularly valued form of work. Surprise!

Rebecca: Since it wasn't niche or special, brewing wasn't considered necessarily a skilled labor. So Bennett writes, quote, "We might respect the brewsters of a village who could carefully prepare the malt, tend the wort, and spice the ale, but they excelled at work in which virtually all women were competent. Skilled they were, but they were not valued as skilled workers." End quote.

Rebecca: Brewing also wasn't organized, since it was something that most women just did at home and were expected to do. So there weren't yet any guilds, and there was just no way to develop a united identity around beer making.

Leila: But after the Black Death, which reached England in the summer of 1348, things started to change in the world more generally. And this became a turning point in the history of brewing as well. More domestic trades started to professionalize, and brewing was one of them. After the Black Death, people in England with a higher standard of living began to consume ale in much higher quantities than before the plague. Even though there were less people after the plague because so many people died, the people that were left were drinking a lot more.

Rebecca: I'm sorry. I'm sorry. It's just #relatable.

Leila: Us having gone through a plague ourselves now, I can give the very unacademically supported theory that maybe these people had just seen some shit and that's why they consumed more ale. I don't know. Science will have to confirm my theory. I have no idea.

Leila: Anyway, the higher demand for ale brought big changes to brewing. Commercial brewing expanded, and as a result, both domestic brewing and the more casual profit-making, by-industrial brewing declined. Ale sellers—that's a hard one to say for me—and ale houses, those rare people and establishments that just sold beer before the Black Death, became much more common.

Leila: And as people began to drink ale more regularly than before, brewing began to professionalize. And instead of being spread out over the population, brewing became concentrated in the hands of professional, industrial brewers who were capable of sustaining much larger operations than what someone could do in their home. The move away from brewing as domestic practice and towards professionalization had a profound effect on women, who had been at brewing center for such a long time.

Anna: Hm. Sounds familiar.

Leila: Yeah. I wonder where we've heard this story about professionalization and women being left out. We'll have to do some more research.

Anna: I don't know. It's ringing a bell, but I just can't put my finger on it.

Anna: In her book, Bennett shows that not all women were impacted at the same time and in the same way by this process. So single women and widows were hit first by these changes in the trade. Before the Black Death, unmarried women could brew and sell their ale to their communities with varied levels of success.

Anna: But after the plague, it was increasingly difficult to keep up with the demand that professional male brewers could meet. Brewing in much larger quantities required more and higher quality equipment, larger establishments to house the operation, and often a staff, and single women simply did not have access to these things. Single women were at a severe financial disadvantage compared to men. They didn't inherit money, land, and resources like men did. And when they could earn an income, they just didn't make as much as men.

Anna: So without access to the same resources, women on their own could not compete with male-run commercial brewing operations. And on top of that, they couldn't obtain loans, which they would need to buy their equipment. Bennett writes, quote, "Single women and widows were poor credit risks economically as well as legally. The poverty of not-married women undermined their credit. Since they owned less, they could borrow less." End quote. No part of the economic system of this time period was set up to support women in virtually any way at all.

Rebecca: Guys, I think the monster mighta been capitalism all along and its buddy sexism. Just throwin' that out there.

Anna: And he would have gotten away with it, if it wasn't for these meddling podcasters.

Rebecca: Widows had it a little easier than other non-married women because they could say that they were merely running their husband's commercial brewing operation and the husband was just no longer with us. But the days in which widows could have practiced brewing because it was what women did were over. Their practice was now tied to that of their dead husbands.

Rebecca: This does continue to confirm my theory that if you're a woman in the early modern Western world, you should be a middle-class widow. It was just the way to go across the board. It still sucks, but you can just rely on the fact that "No, I'm just doin' the stuff my husband did, so I'm cool." Seemed to have worked out for a lotta ladies. Just sayin'.

Rebecca: Aside from the financial aspects that excluded single women and widows from what was now a larger profession, there were also cultural attitudes that only exacerbated the marginalization. So larger brewhouses required more staff than what one woman could have been able to do in her own home before, and women taking the role of authority as an employer and boss was not one that society was eager to accept. As Bennett writes, quote, "As brewing expanded, it came to require a level of managerial authority that non-married brewsters could seldom command." End quote. So rather than running their own brewhouses, single women and widows were more likely to take on the role of ale sellers or alehouse workers, or more likely they were funneled into other trades altogether.

Leila: Feel like there's a lot going on there. And as historians we're not supposed to say this, but some things just don't change. Some things are the same.

Anna: Yeah. Yeah. They're coming for you now. You just don't seem like management material.

Leila: And, of course, women who lived independently outside the control of a husband just could not be trusted. That was not an uncommon belief about women in the Middle Ages or really any age. But the association between ale, drunkenness, and disorder possibly highlighted the distrust of single women in brewing. For widows the stigma was a little less. Typically older in age, widows who ran brewhouses or alehouses posed less of a threat, and people pitied the financial woes of older widows. There's also a lot going on there.

Anna: But to Rebecca's earlier point, yeah, sure, people pitied them, but it's not like these widows didn't know that and use that to their advantage. We have to remember that, too.

Leila: One of the things that made the older women less threatening than younger single women was older women were not as much of a sexual threat as well. So you could, I guess, trust an older woman running an alehouse or a brewhouse to not allow illicit sex or something on her establishment. Younger single women doing the same were seen as much more of a sexual threat in that regard, too.

Leila: And even though married women felt the exclusion from brewing a little later than single women and widows, they would eventually face the same fate. And initially wives had access to the capital and credit that other women were denied, at least they did tangentially through their husbands. But the leadership roles of brewing in marriage had changed. The husband was becoming the front-facing person of the operation. The wife was just drifting into the background.

Leila: Around this time brewers' guilds were also forming. And guilds served to give brewers a community identity and was a key part to the professionalization of the industry. Membership in a guild required payment and supervision and regulation by the guilds, and guilds were able to set the terms of membership, which often excluded ale sellers and part-time brewers. The membership requirements disproportionately affected women, and the cost of membership excluded poorer brewsters.

Anna: Wives did often join guilds along with their husbands, but they didn't participate in the guild as fully as their husbands, who were granted the full benefits of the guild while wives were partly denied them. So male guild members, for example, had the opportunity to participate in the governance of the guild, to wear its livery, and wives did not. They were just associated with the guild by name through their husband.

Anna: And so these particular exclusions effectively just removed women from the professionalization of the brewing industry. By refusing them the benefit of wearing livery, which is a visual symbol, a public declaration of membership in the guild, women couldn't be part of this identity formation happening among brewers. And by limiting their participation in governance, they couldn't exercise any power in the trade. And there were some exceptions to this exclusion, but really not many.

Anna: And as brewers became professionalized and profitable, women were pushed further into the background. And by 1600, the brewster was rare in England, and the dominance of domestic brewing was over. The decline of women in brewing took place in many places around the world for similar reasons, but obviously in different ways depending on the structures of different societies and their laws and how guilds work and things like that.

Rebecca: So today brewing remains a male-dominated field, as is proven by both statistics and those previously mentioned Instagram pages. A study by Auburn University found that only 29% of brewery workers in the US are women. The word brewster has all but disappeared from the craft. And the, quote, "gender neutral" term brewer refers to both men and women.

Rebecca: Microbreweries and craft breweries, those breweries that work outside the large corporate model and operate independently, have provided women a way back into the industry, with more women running their own breweries and taprooms, but it's still a struggle. The craft has become so masculinized over the centuries that even the embodiment of the work itself is seen through the lens of masculinity.

Rebecca: So brewing is physical intensive labor. And a paper from the journal Work, Employment, and Society points out women brewers in our current day must struggle against the gendered assumptions about the physicality of brewing. Quote, "In male-dominated occupations, women attempting recognition as skilled have to confront the context-specific sociopolitical construct of men as the ideal type of worker and women as the wrong sex. Masculine bodies, by virtue of their dominance, gain a level of invisibility, which further emphasizes women's bodies as divergent from salient gender characteristics."

Rebecca: I think it's also interesting that this also goes into home brewing as well. Home brewing, which that's why it was feminine in the first place, because it happened in the home, is also very masculinized and seen as a masculine hobby. Yeah.

Leila: Yeah. I saw something that described Thomas Jefferson as the first home brewer or the founder of home brewing, which I was like, "Wait, what the fuck?"

Anna: He can't found everything, okay? One dude cannot found all the things.

Rebecca: No. No. Also he was probably bad at it. He was bad at making wine and most other things he tried.

Anna: What a dilettante.

Leila: Yeah. Well, and his wife was probably doing it anyway.

Rebecca: Also that.

Leila: Also his wife also didn't found it.

Leila: So the women interviewed in the paper that Rebecca was talking about explain how they try to blend into the masculine invisibility of the job by accentuating their physical ableness and strength and other characteristics typically seen as male. They downplay femininity in their appearance and clothes. And while some of that is certainly functional, like you don't wanna be wearing flowy blouses or whatever while you're tryin' to stir the big vat, it also keeps their gender from announcing itself so boldly and publicly.

Leila: And even the equipment and tools that women brewers need to use are made for the male body, which not only gets in the way of women being able to perform the work and show that they are capable, it's also a safety hazard and can create unsafe places for women to work. Just another iteration of how we've built the modern world for men.

Leila: The way women were pushed out of the trade is actually pretty complex, and we can't fully do it justice in this episode. But unlike the professionalization of modern Western science, where stodgy old men were writing down, always writing it down, why women shouldn't be included in their societies, we don't really get that bluntness here.

Leila: One of the things Bennett says is that it is those public records. It's not that you have to trace this. It's not in personal writings and diaries and stuff. Especially if it was as commonplace as it was, why would you be writing down that type of thing? So we don't really get that bluntness here, and it's much more subtle, and it makes us look at how patriarchy comes from the top down, influencing all sorts of systems and structures, from the way money and resources are moved around and passed down to the way financial systems operate to the interpersonal interactions between a brewster and a male employee.

Anna: Yeah. And I think the distinction you make between when we talk about the professionalization of science or medicine and the way that women were pushed out of those fields, how different that is from something like brewing, which would be basically ubiquitous. All women, basically, are brewing at this time, and so it really changes the method of analysis to get in there and figure out how it worked because science was constantly documenting itself as a way of justifying itself and building its own prestige in a very conscious way. That's what these fusty old dudes were writing about. That's why they were doing it, to be like, "Ah, we should do science, and we definitely shouldn't let any ladies do it because then they'll make it bad."

Anna: But with something like brewing, everybody's already doing it, and it's just a part of daily life. But I think that it's such an interesting way to look into daily life this way and see how we talk about women being pushed outta professionalized science. We talk about how things that happened in the home we also see as science. And so then this is a really interesting contrast between other processes of professionalization and how those impact women.

Rebecca: Yeah. Your point is interesting 'cause making medicines was also this ubiquitous task, but as science professionalizes and medicine professionalizes, there's this need among the professionalized field to be like, "No, don't trust those lady medicines" that I'm not necessarily seeing in this particular story, where at least from what we lay out here in the research that Leila did for this episode, there doesn't seem to be a "Ladies make bad ale" parallel there. Maybe it is out there. Yeah.

Anna: It's like the pressure comes from a totally different direction. It's indirect and is not specific to brewing because people would be like, "Of course ladies can't wear guild livery. They don't do that in any field. That's crazy. What are you talking about?"

Leila: Yeah. I think the closest thing where we get something like what you were saying, Rebecca, like making bad ale, that I didn't see anything like that. The closest thing was that going back to just general stereotypes about women being untrustworthy if not supervised by a husband or whatever and then having that linked to drunkenness and disorder and stuff like that.

Leila: And there were often brewers and brewsters that were trying to get around regulation of the grain price and the ale and tryin' to make more money than what the regulatory system had laid out. And men and women both did that, but as we move out of the 1300s and into the 1400s and you have those negative stereotypes attached to women and then you also have this idea of cheating customers and things like that, then you get another thing that adds on to. "Maybe she doesn't make bad beer or bad ale, but she's a cheat or a trickster or something like that." Another thing that makes her untrustworthy to buy ale from her.

Rebecca: Yeah. Yeah. It feels much more parallel to, yeah, broader early modern economic change and eventually industrialization change, like the movement of the spinning wheel out of the home and into a factory. It's like it's more like that in some ways. Obviously this is earlier than that. Yeah. There's so much economic history, but in the way that we find interesting and not in the annoying numbers way. Sorry, economic historians.

Anna: The AHA is knocking on both of your doors right now, like, "Excuse me, I heard you talking smack about history."

Rebecca: But it really shows the way that the history of capitalism and economic history and the history of gender and labor are just really intertwined.

Leila: Yeah. I mean, it was capitalism all along.

Anna: Yeah. Yeah. Every time.

Rebecca: Since we were yelling about Thomas Jefferson earlier, I do wanna take a moment—

Leila: Oh, let's do that some more.

Rebecca: Let's do it some more. Hey, we can yell about even more Founding Fathers if you want to.

Anna: It was Thomas Jefferson the whole time.

Rebecca: Anyway, the thing I was actually going to say was I do feel like what's also interesting about this is the way it relates to this physicality of masculinity idea, but also how we visualize history and how we see contemporary things relates to how we visualize history. In Philadelphia we're a grungy, hipster-y city. That's one of the reasons I like it here. And there is a growing microbrewery—it's still fairly new in Philly, but there's a growing number of them. And a lot of, though, the branding around beer in Philadelphia is about history, is about Founding Fathers, is about Ben Franklin.

Leila: Oh, Philly.

Rebecca: Yeah. I know, I know. We've got one thing, and we put it everywhere.

Leila: Yeah, damn.

Anna: It's just gritty and Ben Franklin all the time.

Rebecca: Yep. Yep. Gritty, Ben Franklin, the Liberty Bell, and people yelling about versions of the Liberty Bell that are incorrect. That might just be my social circle because I hang out with historians.

Rebecca: And the biggest, most obvious version of this, Yards Brewing Company, has these Founding Fathers beers. And I don't even know if they can be considered an independent brewery 'cause they're pretty big. Maybe they are. But even smaller breweries will tap into this Philly history, Ben Franklin thing in this way that ties contemporary grungy post-industrial hipster Philadelphia to old history white dudes. And as we've laid out in this episode, it is fair to say that by colonial America times, that was terrible. That was terrible.

Anna: The AHA is sending a SWAT team to your house right now.

Rebecca: By the 18th century, when people like Benjamin Franklin were around, this was already a masculinized field, so it's not historically inaccurate to call that history masculine necessarily, but it is reflective of this idea that then women get totally erased from this story and this history in this way that I think is interesting and frustrating.

Anna: Yeah. I think American beer culture is very strange just generally, and there's a lot of stuff there that you could talk about.

Leila: Like the Manhattan Brewing Company in Texas that actually has a beer called Bikini Atoll.

Anna: Okay. All right. I think that the podcast is over now 'cause I gotta go just sit down and think about that for a while.

Leila: All right. Good-bye, everybody.

Anna: We're never coming back 'cause I learned about the nuclear bomb beer. Ooh, boy

Rebecca: Everything that makes you angry just intersected in a beer name, Anna.

Anna: I know. I'm shell-shocked. I don't know what to say.

Leila: Well, if you liked our episode today, leave us a rating and a review on Apple Podcasts so that new listeners can find us. If you have questions about any of the topics we discussed, tweet us at @ladyxscience or #LadySciPod. For show notes, episode transcripts, to sign up for our monthly newsletter, read articles and essay, pitch us an idea, and more, visit ladyscience.com.

Leila: We are an independent magazine, and we depend on the support from our readers and listeners. Please support us through a monthly donation with Patreon or through one-time donations. Just visit ladyscience.com/donate. And until next time, you can find us on Facebook at @ladysciencemag and on Twitter and Instagram at @ladyxscience.

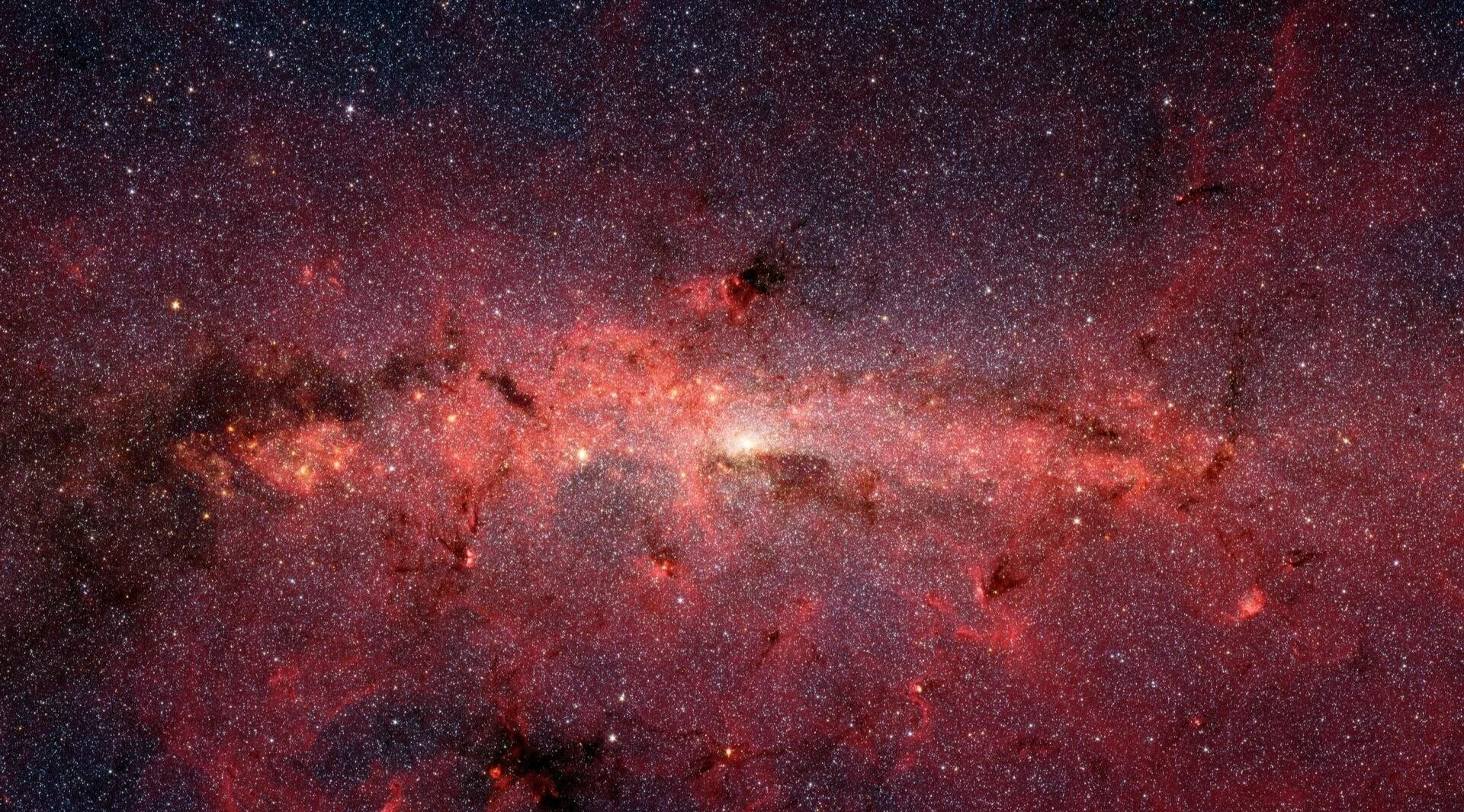

Image credit: Egyptian hieroglyphs showing women pouring beer (Wikimedia Commons | Public Domain)