"Ways to please a lady": Advertisements for the Modern Kitchen

The internet seems to love vintage advertisements from the 1940s, 50s, and 60s, as evidenced by the numerous articles and listicles about such ads that circulate social media. Perhaps it helps us all feel a little bit better about ourselves that we’re able to ironically poke fun at the blatant racism and sexism of midcentury ads: “At least we don’t do that anymore!” The sexism of midcentury America is most obvious in advertisements centered on house and home. These advertisements would have us believe in a world where women find deep, personal fulfillment in cleaning toilets, men can make casual threats of domestic violence, and women of color don’t exist (seriously, this is the whitest America). Such surface level observations about midcentury advertisements that those articles and listicles make are, to me at least, unremarkable. What I’m interested in is the gender politics inherent in the capitalist medium of advertisements and its relationship to the domestic technology that is on display.

Within advertisements of kitchen technology, specifically, I see a clear division between those directed at women and those directed at men. Advertisements for kitchen technologies directed at women emphasize ease of use, affordability, and efficiency. Take, for instance, this 1945 ad for a Kelvinator “Automatic Cook.”

This product promises women the ease of cooking a full dinner just by pushing a button on an oven timer--a button which the advertisement text calls an “electric ‘brain’.” With the ability to “Set It--And Forget It,” the product also offers women the freedom to leave the house; after an afternoon out, this housewife comes home, sets aside her handbag and white gloves, and simply takes a perfectly cooked dinner out of the oven.

Wear-Ever Pressure Cookers not only promises efficiency, but also affordability.

While the dead-eyed husband is daydreaming of food, the woman is calculating budgets in her head: “[It gives] welcome relief to my hard-pressed food budget. It makes economy cuts of meat deliciously tender and saves fuel too.”

In a 1960 advertisement, Hotpoint advertises their appliances’ efficiency-- “Saves Time--Saves Steps--Saves Work.”

On the left page in bolded text, the ad states: “Hotpoint- First To Introduce A Complete, Smartly Styled, Custom-Matched, All-Electric Kitchen With Scientifically Planned Work-Saving Centers!” The woman is pictured in action--cooking, loading the dishwasher, etc.-- with a caption below each that explains how the woman is saving time and work with those specific appliances. On the right page, in the bottom left hand corner, the ad includes an actual blueprint of how the kitchen should be laid out for maximum efficiency. The caption to the right of the blueprint explains that this design is ideal for “modern women.”

Obviously, these advertisements are sexist; they at once romanticize and trivialize women’s domestic work. However, there is much more going on here than that. The demand for ease-of-use, efficiency, and affordability influenced and shaped the technology and engineering behind the ad--the technology and the design of kitchen appliances were constructed through the purview of women’s lived experiences. While advertisements, on one hand, tell consumers what they think they should need, consumers, on the other hand, play a key role in telling the corporations and marketers what is working and what is not. In the case of kitchen appliances, women are the main consumers.

In both the Wear-Ever and Hotpoint ads, the marketers understand that women, more so than their husbands, set the budgets for their families. While the husband typically brought in the money, the wife managed it. So an appliance’s affordable price tag or economic use of resources, fuel, and electricity appealed specifically to a female consumer. In the 1940s, the housewife served as an economic authority not just of her own house, but also of the nation at large. Federal organizations such as the Department of Labor, and labor organizations like the American Federation of Labor and the Congress of Industrial Organizations, relied on self-reported data from housewives of all social strata to calculate the national cost of living. This, in turn, influenced the national price tag of food and other consumables.

The selling point of efficiency, which is most prominent in the Hotpoint ad, draws on decades of research in scientific management. Scientific management analyzes workflows in conjunction with methods of work and production with the purpose of maximizing economic efficiency and labor productivity. Experts like Frederick Taylor, and Lillian and Frank Gilbreth, pioneered the field of scientific management in the 20th century, and many women writers of home economics text books and manuals appropriated many of its principles for women and the home. Scientific management of the kitchen was an all-encompassing endeavor. From the physical placement and design of kitchen workspaces, to the range and motion of the female body interacting with these workspaces, all are displayed in the Hotpoint ad. These selling points aren’t arbitrary, but are reflective of women’s experiences. Engineers observed and analyzed real women at work in these spaces, and their results shaped the design and efficiency of the machines themselves.

A subtext that all three of these ads share is an understanding, superficial perhaps, that women don’t really want to spend all their time in a kitchen. A selling point for each product is the time away from the kitchen that the appliance provides through its ease-of-use or efficiency, a concept that extended far beyond the three ads here. Kelvinator promises an afternoon out and about, perhaps with friends or running errands; Wear-ever guarantees more free-time; and Hotpoint wants to release women from the “drudgery” of kitchen work in order to delegate more time to other duties. Oddly, these ads romanticize women’s work in the kitchen, but this romanticization is constantly placed in tension with the underlying desire to leave the kitchen.

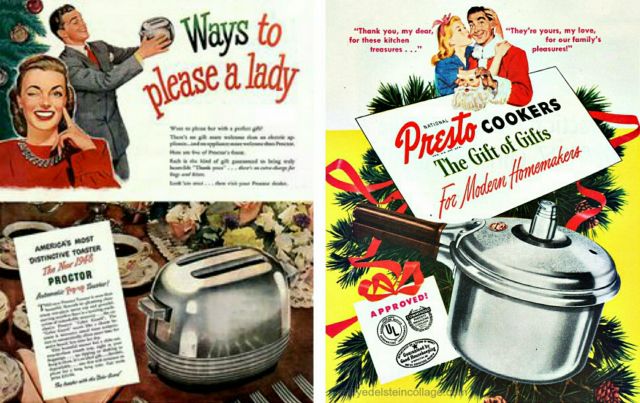

In kitchen advertisements directed at men buying gifts for their wives, the ads lose much of their complexity. They don’t feature efficiency or affordability; instead, they bizarrely focus on sexual pleasure.

Even at a glance, we can see that these ads are not nearly as involved as the ones meant for women: they contain much less text and the visuals are mostly for aesthetic appeal. Where the advertisements meant for women attempted to speak to various aspects of their lived experiences, the advertisements meant for men play on the husband’s assumptions that women enjoy, and garner pleasure from, being chained to the kitchen in the service of her family. These ads completely obscure the difficulty of domestic work, trivialize female sexuality, and remove women as the economic authority of the home.

Despite the differences between the advertisements’ female and male audiences, what the ads share is a concept of modernity that is fundamentally tied to women. These ads are prescriptive in that they imply women are responsible for modernizing their homes and their families, both technologically by partaking of labor-saving machines and aesthetically by incorporating high tech materials like stainless steel and electronics into their kitchens. Typically, we view the midcentury housewife through a lens of nostalgia, as a throwback identity that sought to reclaim some sense of postwar innocence. In reality, however, women in the home were expected to keep up with the fast pace of technological change. Through scientific management of the home, they were expected to participate in and practice modernity like any male engineer. Whether a woman decided to buy the appliances for their efficiency, or if a husband decided to buy an appliance to “satisfy” his wife, the industry of kitchen technology relied mainly on the buying power of women as consumers of production. Much more than reflecting an antiquated form of midcentury sexism, these advertisements reflect a vision of modernity with women at its center.

Further Reading:

Ruth Schwartz Cowan, More Work for Mother: The Ironies of Household Technology from the Open Hearth to the Microwave (Basic Books, 1985).

Thomas A. Stapleford, “‘Housewife vs. Economist’: Gender, Class, and Domestic Economic Knowledge in Twentieth-Century America,” Labor: Studies in Working-Class History of the Americas 1, no. 2 (2004): 89–112.

Image credit: St. Charles Kitchen, recipe for Kitchen Perfection, 1955. Curt Tiech postcards (Wikimedia Commons | Public Domain)