Sewing Science, Sewing History

The sewing room was always awash with color. Bolts of fabric laid across the many sturdy wooden desks and metal drafting tables, offering hints of the clothing they would become or merely adding to the beautiful chaos. Tiny plastic cabinets were filled with thread, and needles, and scissors, all precisely organized. The sewing machine in the corner was an inelegant, boxy thing, solid and practical. With its harsh-looking needle and dozens of dials, I could tell that this was a device meant to get work done, not a family heirloom or a museum piece, meant merely to invoke nostalgia for a simpler time.

My grandmother was a lot of things: a storyteller, a child of the Dust Bowl, a post-World War II housewife who spoke out against racism but raised her family in a redlined Southern California suburb, an atheist who grew up surrounded by conservative Presbyterians, an eventual victim of Alzheimer’s disease. Each one of these identities is a story unto itself. But deep in the hearts of the family and friends who knew and loved her, she is probably most remembered as a seamstress.

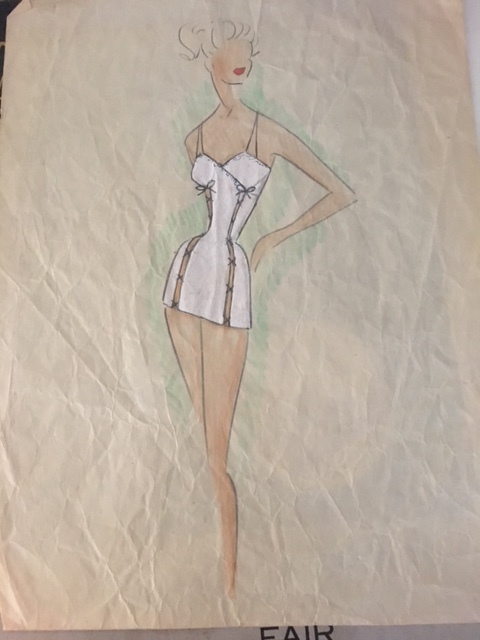

To this day, my grandmother’s sewing skills are spoken of with a sort of awe. My mom and I both joke that we are too intimidated to improve our sewing skills because we know we will never be as good as she was. Otherwise a disorganized free spirit with a penchant for conversational tangents and a habit of misplacing her belongings, Alene Hill became eagle-eyed and meticulous when cutting a pattern. Although wary of digital technology, she knew exactly how to program her sewing machine to deliver the right kind of stitch. When my mother was growing up, my grandmother made most of her clothes, while also working as a pattern maker for Rose Marie Reid, a bathing suit designer known for its glamorous styles. Though she was paid barely enough to cover the babysitter for her two children, she was a talented engineer of the most feminine of clothing: pastel-colored, ruffled, figure-skimming one-pieces.

Engineer. There’s something strangely thrilling about referring to my grandmother that way, using such a prestigiously practical title that was never bestowed on her in life. Coincidentally, her husband, my grandfather, was called an engineer. As an aeronautical expert he worked for the military industrial complex’s most recognizable companies, including the Northrup Corporation and the Lockheed Aircraft Company, on projects that included the early space race efforts in the late 1940s at Edwards Air Force Base.

At EAFB, my grandfather and his compatriots sought to determine the amount of gravitational force the human body could tolerate. The research project was led by Dr. John Paul Stapp, who some say, in reference to the tests my grandfather and his fellow engineers were tirelessly running in California’s Mojave Desert, once declared, “Whatever can go wrong, will go wrong.” Stapp named this axiom “Murphy’s Law” after another Air Force engineer, Captain Edward A. Murphy. The “Murphy’s law” story could very well be balderdash, but it’s emblematic of the way my family talks about my grandfather and his career. He was engineering’s Forrest Gump, an everyman found (sometimes literally) at the edges of photographs taken during significant historical events.

But my grandfather wasn’t the only engineer in the family. While he was playing a small but significant role in redefining man’s relationship to the stars, my grandmother was using similar skills like modeling, scaling, and spatial problem solving to change women’s fashion.

Famously inspired by Christian Dior’s “New Look,” women’s fashion took a decidedly feminine turn following World War II, exchanging manly square shoulders and unfussy suits for full skirts, girlish Peter Pan collars, and pearls. Made of newly invented stretch fabrics that showed off the female form and decorated with ruffles that mimicked couture blouses and ballgowns, the bathing suits Alene Hill designed followed those same trends. Along with making their clothes more feminine, women of the post-World War II era were expected to make their lives more feminine as well by giving up social and economic independence found during the war and “returning” to the status of wives and mothers.

The promise of manned spaceflight encouraged men and women to dream of life among the stars, but fashions reminded them that even in that high-tech future, gender roles would maintain their Jetsons’-like traditionality. Engineers like my grandparents played a role in shaping both sides of post-World War II society, though only one of them was ever called an engineer in life.

Designing new fashion was a science in its own right. The bathing suits made under the Rose Marie Reid label were known for their technical and stylistic innovations. The company was the first to include built-in foundational garments and to manufacture suits in a range of dress sizes. While my grandfather and his coworkers built machines to simulate spaceflight, my grandmother and her fellow seamstresses puzzled out how to make bathing suits that fit a larger range of body types than their competitors offered, ones that were more structured and more stylistically embellished. To solve these puzzles they made scientific and technical choices in experimenting with new materials, and adapting their tools. They had to be engineers, but because their work fit within the overlapping spheres of domesticity and fashion, they do not fit as neatly as my grandfather did into narratives of space age innovation.

I’m not the first person to suggest that we re-examine domestic, feminine-coded activities like sewing through the lens of science and technology. In 2015, scientist and education researcher Stephanie Vasko critiqued STEM educators for emphasizing high-tech “maker” activities like coding and 3-D printing at the expense of low-tech activities like gardening, cooking, and, yes, sewing

While these appear to be divided along lines of added technology, these activities could be seen as being divided along traditional gender lines as well, with handicrafts places squarely in the low-tech category. This idea that low-tech and high-tech are entirely separate is misleading: Traditionally low-tech activities can be incredibly important for enhancing STEM education, and there is much more interplay between advances in technology and in crafting than you might think.

To re-imagine what it means to do science, technology, and medicine is to re-imagine who gets to count as a STEM professional. And this reframing of science and technology is central to the work of feminist historians of science and feminist theorists of science. It allows us to think about the way technology (and diverse technologists) shaped fashion and politics, culture and war. But what if we bestowed those titles on not just theoretical women, or historical women we never knew, but also on the women in our own lives, on our grandmothers, and aunts, and cousins? What if I started calling my grandmother what she really was?

What if I called up my mom tomorrow and said, “Mom, both your parents were engineers”?

I think I just might do that.