It shouldn’t have taken so long to recognize the work of women historians of science

Reading like an emergency at the tail-end of Women’s History Month, a Nature op-ed from March 24, Women must not be obscured in science’s history, canvasses the field for a look at upcoming and ongoing projects on women in the history of science, as though at last the tide is beginning to turn on a history that has been largely dominated by histories of great men. “Initiatives are now under way to right this wrong,” the author writes.

I take issue not with the historians and initiatives mentioned, which are extremely rad, but with Nature’s framing of their work as the field finally getting around to women. It obscures researchers, such as Marilyn Ogilvie, Margaret Rossiter, and Darlene Clark Hine, who have been working on this since at least the 70s. What’s more, it glosses over the fact that work on this subject hasn’t made it into the public consciousness not because it doesn’t exist but because it doesn’t get funded. It also gets mocked at conferences, and researchers are dissuaded from devoting their careers to “niche” subjects. (Don’t even get me started on creating or adapting your work for general audiences and how far that will get you in the cutthroat race to have a job that provides health insurance).

In the fall of 2016, my co-editor and I Leila McNeill presented about Lady Science at the Society for Literature, Science, and the Arts in Atlanta. The conference was held jointly with the History of Science Society Annual Meeting (and the Philosophy of Science Annual Meeting). We historians of science are a small bunch—you can fit three of our societies into one downtown hotel. We reflect on this particular conference appearance often because it was the one where Ogilvie and Rossiter were in the audience.

For those of us who study women (even though that should be all of us), they are giants and inspirations and the authors of foundational works of recovery, bibliography, and biography. Ogilvie’s first “Biographical Dictionary of Women in Science,” co-authored with Joy Harvey, was published in 1986. Rossiter’s “Women Scientists in America, Struggles and Strategies to 1940” came out in 1982. After our presentation, Rossiter told us we were doing good work, but it is work that shouldn’t still need doing after all these years—that it was disappointing Lady Science had come into a world that seemed to have made so little progress on the work that she and her colleagues began. So Nature declaring earlier this month that “initiatives are now underway to right this wrong” came as a surprise for those of us who have been doing that for quite some time now.

A couple of years after the Atlanta conference, we invited Ogilvie on the Lady Science Podcast to talk about her long career and her inimitable contributions to the history of science. It was an honor and a true joy. Ogilvie is now emerita at the University of Oklahoma, where Leila and I went to grad school, and she talked to us about the serendipity of her path into the history of science, the struggles she faced collecting sources for her books and biographical dictionaries, and the pushback she received from the field.

She reiterated two of the most important tenets of this research—the same tenets that form the foundation of Lady Science. First, to adequately capture the history of women in science, we must expand our definitions of what counts as science. “We talk about not just what the actual theoretical science is,” Ogilvie says, “but all of the things that make this science possible, and so many women are involved in that.” Second, the history of women in science is not, and cannot be represented, as a niche. “Their place is there. It is not an isolated sub-section of it, but I think it is a very integral part of the history of science.”

I’ll add one more tenet, something that we have always tried to observe at Lady Science and in our individual work. The history of women in science is a living breathing thing, created and maintained largely by women who have been working against a disinterested, male-dominated field for decades. If we do not preserve their stories in our efforts to recover the stories of women scientists, we do a disservice to them, to the field we love, and to all we hope our work as historians can do for an equitable future for science.

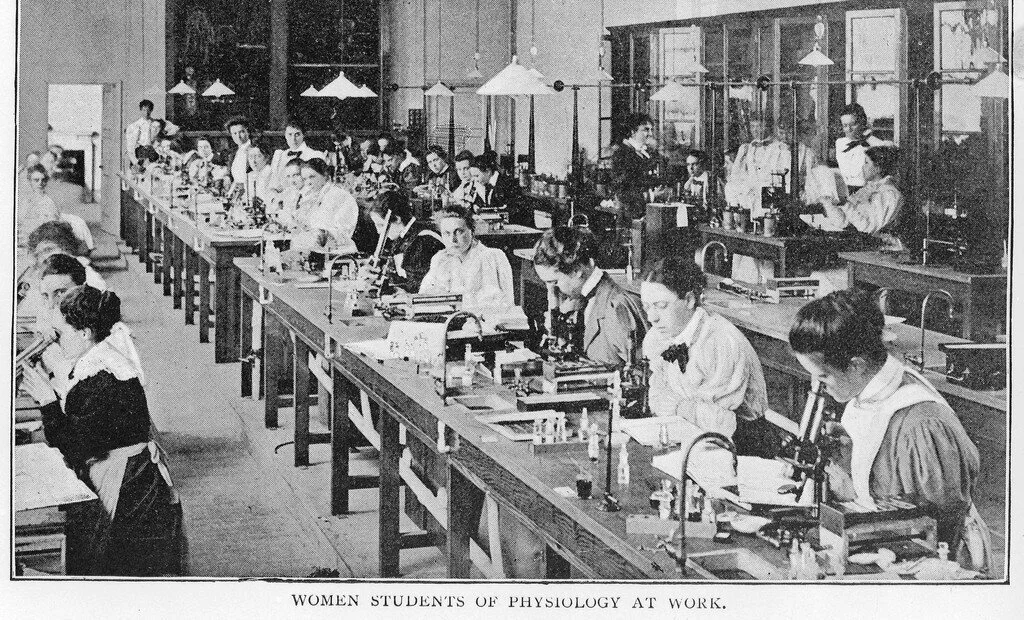

Image credit: The London School of Medicine, Physiology Laboratory. Women’s Students of Physiology at work, 1899. (Wellcome Collection | Public Domain)