Women Scribes: Technologists of the Middle Ages

In the early Middle Ages, Western Europe was home to a growing number of monasteries and convents. Far from being places of rote worship, these religious houses sparked an explosion of scientific research that transformed European life. Since this was an era before the printing press, writing was an essential technology that allowed information to be communicated across long distances, most often in the form of books. At the center of this project were scribes, many of whom were, perhaps surprisingly, women. Their highly specialized labor, complete with its own education, tools, and practices, was only part of a centuries-long process of experimentation and refinement.

Writing has been a part of societies for so long that it may seem odd to think of it as an innovative technology, but it has been a central force in shaping human history. Technologies are like extensions of our bodies: cars extend our ability to move, phones extend the range of our voices, a pair of glasses enhances our vision, and writing enhances our memories and extends the distance we can communicate. For example, the earliest written script, Cuneiform, invented in Mesopotamia around 5,000 years ago, was primarily used to record inventories of goods, enabling people to trade across long distances. As with some digital technologies today, which now allow us to communicate on a global scale, writing provided a means to store and communicate information, leading to several “renaissances” in the Middle Ages.

Book-making and ink-making, as integral components of writing, were, and still are, technical processes. Book-making began by slaughtering and skinning animal, usually a cow, calf, or goat. After selecting skins with as few blemishes as possible, a parchmenter soaked them in a chemical solution, typically a mixture of water, barks, lime, or human waste, to loosen the hair and flesh. Once the skins were ready, they would be painstakingly scraped to remove the animal’s organic matter; the skin would then be stretched and dried until it would be ready for the scriptorium. Ink underwent a similarly technical process, as it was often the result of a multi-day process of steeping and simmering nuts or barks to arrive at the desired consistency and color.

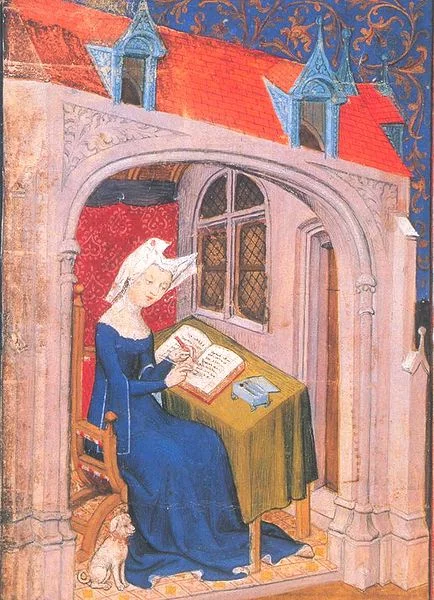

Today, most popular representations of manuscript production and scriptoria depict exclusively male spaces. Whether it be Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose, Game of Thrones’ Citadel, or the board game Biblios, the image that “scriptorium” conjures up is that of robed men laboring over texts. Yet, women had a very real place in developing, maintaining, and innovating this arduously crafted technology, using it to share visions, communicate with each other, and create works of staggering beauty and insight.

History celebrates a handful of exceptional women from the Middle Ages, like Hrotsvit of Gandersheim (10th century), whose plays are the first of which we know written by a woman in Western literature; Hildegard of Bingen (12th century), who innovated with musical composition; and Christine de Pizan (14th-15th century), a prolific late medieval author. They are frequently feted, and all have settings at Judy Chicago’s Dinner Party in the Brooklyn Museum. But there were others—scribes, nuns, and religious women—who were using the technology of writing to serve their own communities. Though working as a scribe in a scriptorium might appear to be a more mundane aspect of intellectual life, women who worked in these roles were on the front lines of medieval intellectual life.

Although some writers have left behind well-preserved records, the evidence for women’s writing is difficult to track across the period. Authorship was typically anonymous, and there are few sources that detailed the production of manuscripts. There would be little doubt that literacy and writing, which were taught separately at the time, were predominately male. But if we look at how, not just what, women wrote, edited, and communicated, we can see patterns that suggest women had a broad intellectual presence throughout the period.

In Anglo-Saxon England, for example, religious women had an inclusive place in the world of writing. Women were often educated alongside men in “double-houses,” or co-ed, monasteries and schools. One such monastery is that at Whitby, which was founded and overseen by Abbess Hild in the 8th century. Hild, who was later sainted, would have overseen the daily life of the monastery as well as its teaching and copying of books. Archaeological excavations at Whitby, as well as a convent at Barking, have found abundant styli, the main tool of students, suggesting that there was robust scribal activity or education that included both women and men.

Some highly educated women regularly corresponded with members of the church, as evidenced by Eadburga, abbess of Minister-in-Thanet, who wrote to St. Boniface while he was working as a missionary to Europe in the mid-8th century. In their correspondence, he asks her and her community to copy a luxurious book, a major activity that scribes undertook in an era before printing. Eadburga was hardly likely to be the sole writer in her institution; in fact, her pupil Lioba went on to become an abbess of her own monastery, an indication that Minister-in-Thanet may have had a bustling school and scriptorium. These abbess’ careers were not isolated examples, however. Archaeological and paleographic evidence suggests that St. Mary’s Abbey in Winchester, a major religious and political center, produced copies of texts ranging from prayerbooks to versions of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle.

In many cases, however, writing was a tool to exclude women. Prayerbooks and church documents were often written for a default male reader, indicated, for example, by use of “monk” instead of “nun.” Such male-centered rhetoric signified who had access to religious texts and who was the envisaged member of a religious community. Countering this erasure, women literally inscribed themselves into manuscripts. In the Salisbury Psalter, a 10th or 11th century prayerbook, nuns appear to have replaced masculine-inflected words with feminine ones, suggesting that the book was adapted for use by a community of women. Where an original prayer read, “famulum tuum” (“thy servant”), it was rewritten with “famulam tuan” (“thy [female] servant” or “handmaiden”). Likewise, an Old English translation of the 10th century Regularis Concordia, a major text establishing the rules of monasteries in England, underwent similar alterations, with seo abbod (“abbott”) modified to read seo abbodysse (abbess), among other changes. Other manuscripts have shown signs of similar repurposing of male-generated texts. Without writing (or re-writing), these women would have been isolated, worshipping from books designed for men. By learning the craft and wielding the tools of book-making, they were able to play roles in the development of medieval thought and society.

If we broaden our definition of what “writing” means to include the entire process of making a book, we find women further pushing against social norms to share their lives and experiences. Hildegard, who received holy visions, directed the making of her books, even if she did not perform the labor of writing. This image from her Liber Scivias depicts her receiving a vision from God in the form of flames, and dictating to a monk, who copies her words while she is making sketches on a wax tablet. Another well-known example is that of late-medieval English mystic Margery Kempe, who dictated details of her life and conversations with God to a scribe and a priest. The resulting Book of Margery Kempe, is often regarded as the first autobiography in English.

With the rise of white supremacists claiming the middle ages as the model of a successful white, male-oriented society, scholars have been mounting a burgeoning effort to highlight the diversity of medieval European life. Historians have emphasized, for example, that the people we call “English” were actually immigrants, that Africans were known to live across the continent in the period, and that Europeans traded extensively with Middle Eastern countries. Rather than occupying a small, confined corner of intellectual life, women as copyists and scribes and dictators were a constant presence in the period. There is even a high likelihood that the only reason why we have the Anglo-Saxon classic Beowulf is the labor of a female copyist. By challenging ourselves to reassess how we think of women’s work in making the medieval world, we are not only coming to a greater understanding of the past, but fighting for justice in the present.

Further Reading

Benedict, Kimberly M. Empowering Collaborations: Writing Partnerships Between Religious Women and Scribes in the Middle Ages. New York: Routledge, 2004.

Michelle P. Brown. Anglo-Saxon Manuscripts. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1991.

Michelle P. Brown, “Female Book Ownership and Production in Anglo-Saxon England: The Evidence of the Ninth-Century Prayerbooks.” In Lexis and Texts in Early English: Papers in Honour of Jane Roberts, edited C. Kay and L. Sylvester. Amsterdam: Brepols, 2001: 45-68.

McKitterick, Rosamond. “‘Nuns’ Scriptoria in England and Francia in the Eighth Century.” Francia 19.1 (1992): 1-36.